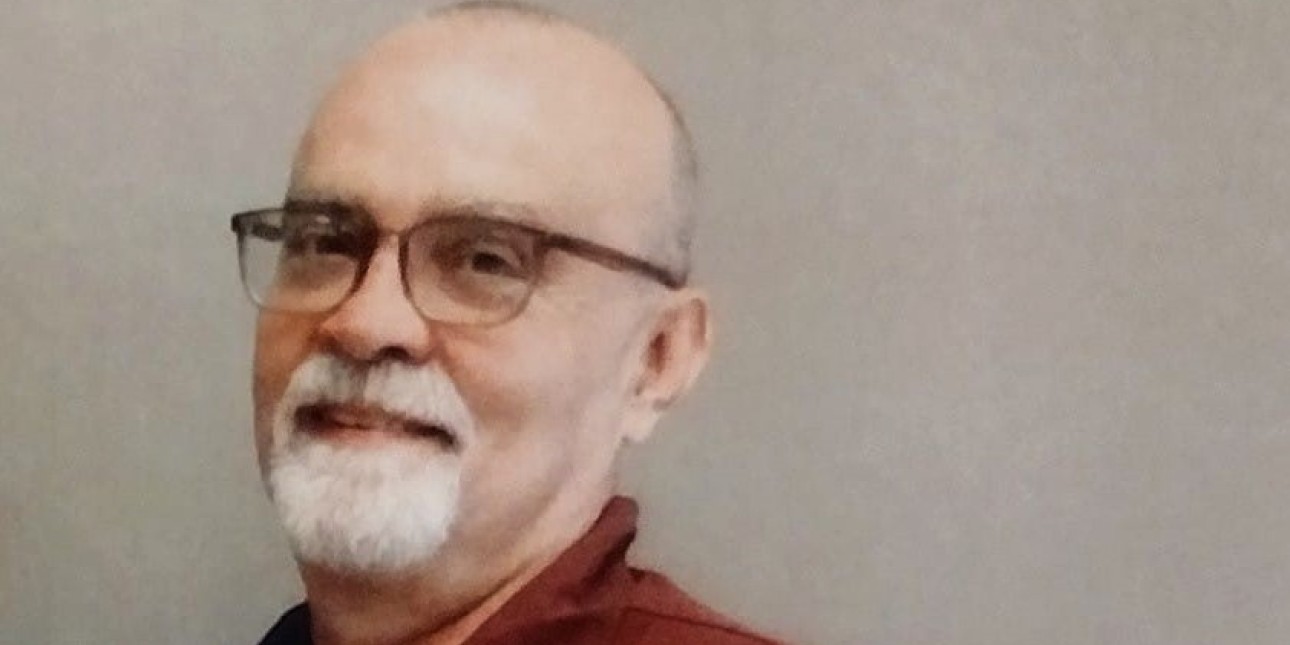

The Artist: Tom Schilk

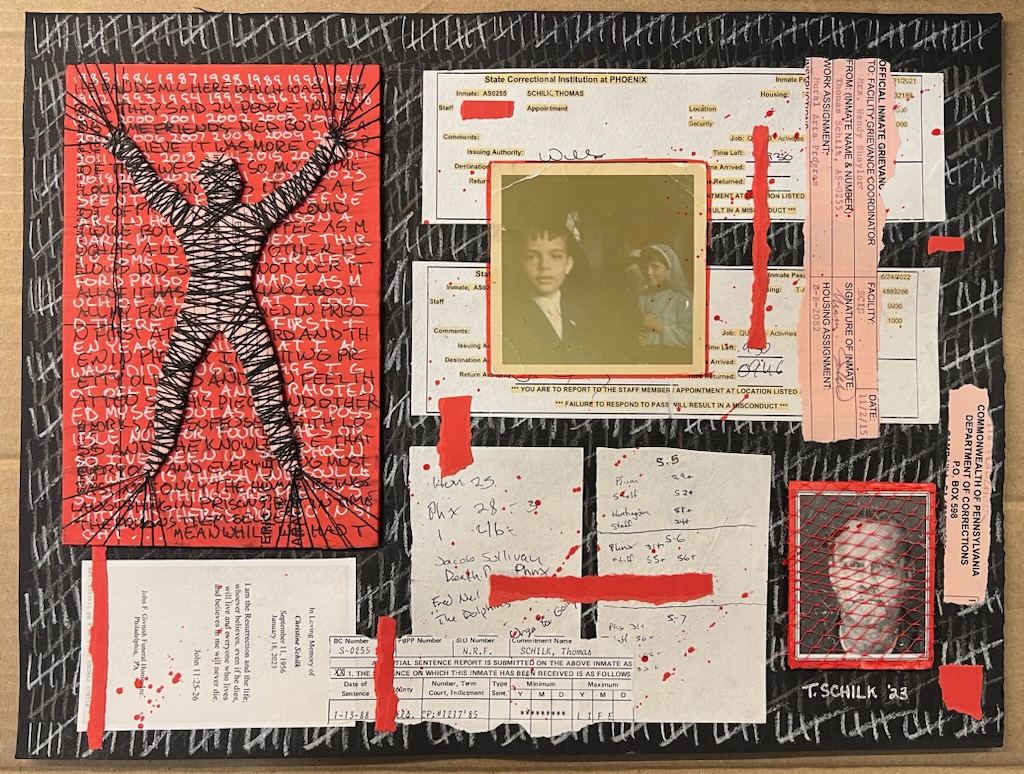

Tom Schilk was born and raised in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia. Tom has many interests including art and writing. His work has been exhibited at many venues including The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Barnes Foundation, The Theater of The Living Arts, and various Universities. His essays have been included in the curriculum of West Chester University, Villanova University, University Of Penn, and Princeton University. For the time being, Tom lives and works at SCI-Phoenix.

This is an ongoing story that will be told episodically. Scroll down to listen to a playlist Tom created to accompany this piece.

It was summer and outside my window I could hear pigeons cooing on the wire. Across from our little row house, the looms of Devon Mills were whooshing and clacking, and nearby I could hear the happy shrieks of children playing in the streets. I hurried to join them.

In the of summer of 1969, I was almost ten and enjoying the recent departure of my father. While it was good that he left, my mother would now struggle to take care of the five of her seven kids still at home. A waitress/barmaid she did whatever was needed to keep a roof over our heads and food in our bellies. Around that time, I started to realize that we didn't have much money.

My brother Joey was eighteen months older than me, and we spent a lot of time together. Scrambling for money, we tried everything from washing cars to selling newspapers. We would check the coin returns from every phone booth, pack people’s bags at Penn Fruit and, at the local laundromat, Joey would tilt back the washing machines as I felt around underneath to see if anybody dropped any coins. Finders, keepers!

Back then, Kensington was a hard-knuckled neighborhood full of working class and poor people, though we didn't think of ourselves that way. Bars littered the neighborhood and bakeries were plentiful too. Both got some business from our house. Along with Devon Mills, factories darkened most streets, and the mostly low-paying jobs were enough for people to maintain but not improve their lives. Factories like Caledonia Dye Works, Clover Mills, Jo-Mar and countless others swallowed up my neighbors at daybreak and spit them back out at night. Even as a kid, I knew I didn't want to wind up like that. There were many environmentally hazardous plants in the neighborhood too. We lived on Westmoreland street and the same street held the foully belching Senn Chemical and Masland Duraleather with its 55 gallon drums of toxic chemicals unsecured out front.

Back at home, I laced up my dirty sneakers and ran towards the door.

*****

Some wanted to know why it was good that my father left. Here's my sort of answer. Before my father left, I remember how he would sit on the couch every night to watch TV and drink his beer. He especially liked to watch movies about war. The right end of the couch was his and no one else was allowed to sit there. Next to him was an end table with a lamp, placed toward the back, which sat on a small round lace doily. On the front of the table there was a small, square, clear glass ashtray that also was his. I remember that the ashtray started clean every night then filled up with crinkled Pall-Mall butts as the night wore on. Closest to his hand was his beer glass, which looked like it was made from the same glass as his ashtray. His beer glass sat on a round cork coaster that he replaced every night. The coasters were advertisements for Piels, Blue Ribbon, Ortliebs, or some other beer. My father drank Ballentine’s. He got the coasters for free from one of the many local tappies that crowded our neighborhood.

Most nights, my brother Joey and me would lie on our thin carpet, in front of our father, and watch TV. Not that we always wanted to. I remember that all the lamps would be turned off and the scenes on our black-and-white TV flashed through the living-room like blue lightning. We weren’t allowed to make any noise, so we lay frozen as the bombs dropped and the bullets whizzed by. Some nights, he would say, “Here, you want some beer?” and I would take the clear glass with both hands and drink a little of the warm, sour liquid. Joey always drank more than me. Although I can’t remember the first time I took a drink, I remember it tasted like something had gone bad.

Awhile after my father left—I was ten years old—I remember Joey and I came up with the thirty cents it took to buy us a quart of Ortlieb’s beer on New Years Eve 1969. Even though I drank less than half—Joey drank the most—I got sick and vomited in the alley behind our house. When I was twelve, I drank a whole quart of Bali Hai wine on the loading dock of Masland’s Dura-Leather right around the corner from our house. It was as fruity pink syrup that cost a dollar and was worth just about that much. I remember laying flat on my back and experiencing my first case of the spins. I vomited so much and made all kinds of promises to God that I wouldn’t keep. I remember, throughout my teens, Joey, me, and our friends would put our nickels and dimes together to buy cheap wine. Boone’s Farm Apple was a favorite because it only cost ninety-four cents a quart.

When I was sixteen, at a Christmas party over the McMenniman’s house, I drank almost a fifth of Seagram’s lime vodka and I remember holding my new leather coat away from my body as I vomited on the pavement. I remember the molten heat that filled my chest after downing shots of Ron Rico 151 at Michael DeComa’s house and all the nasty hotdogs that I ate afterward.

In my early twenties, Mary and me would smoke copious amounts of weed and then make all kinds of sugary concoctions in our Waring blender. We’d mix Bacardi Silver with strawberries, pineapple, kiwis or other fruit with crushed ice and always Goya crème de cacao. The best part was licking her sweet sticky lips.

I remember the darkness as Mary and me drove in the back of a van to Jenkintown with her pretentious friends. I remember the musky taste of the Puna Butter sinsemilla and the crisp, dry, bite of St. Pauli’s Girl that they handed back to us. I remember all the watery bottles of cold Miller’s that I drank while waiting in some diver bar for whoever my connection was at the time. And I remember downing shots in the hushed silence of a bar in Esplanade Boulevard in Metairie Louisiana right before the FBI caught up with me. From my late twenties until I was 35, I remember tasting a lot of vinegary jail-house wine that I would cook up and sell for cop-money. I remember about eighteen years ago, when I made my final gallon of jail-house wine from two pints of sugar, fresh orange juice, one sliced potato and five days’ worth of impatience. It was my last drink and it tasted like something that had gone bad.

Now I’m fifty-three and still I remember most things. I remember lying in my cell and wanting to die night after night after night. I remember all the trips to the hole. I remember when I first came to prison and how the cell block seemed to go on forever. I remember the crackle of the match against the striker and the smell of sulfur when I cooked up the dope. I remember my body shivering on that cold December night when I found out that Mary was gone forever. I remember my clothes stinking of the stale smoke from all the diver bars that I half lived in then. I remember my Ohaus triple-beam scale and the weed and the baggies and the rush of the hustle. I remember the power I felt when some sweet young thing shook her ass at me while George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog” throbbed out of the jukebox in Tellup’s Bar. I remember the taste of Mary’s lips and how her hair looked spilled out on the pillow. I remember being afraid she would fly and the purple bruises on her arms when I held on too tight. I remember the limp Christmas decorations that hung on for way too long the year we lost Joey. I remember the Roger Dean artwork on the cover of the Yes album that I cleaned my weed on. I remember not eating hotdogs for almost ten years. I remember how good I looked in my three-quarter length brown coat. I remember all the promises that I didn’t keep. I remember how the fake fruit taste of Bali Hai was strong enough to cut through the bitter taste of vomit in my mouth. I remember when Ortlieb’s went up to thirty-five cents a quart. I remember finally, really believing that my father wasn’t coming back anymore. I remember the rough feel of the threadbare carpet against my bony knees and elbows as I laid on the floor and how hard it was to stay still. I remember Joe’s eyes looking into mine as I drank the warm flat beer and the crack of the belt. And I remember he yelped as we watched a blue soldier take a round to his chest and the precise curve of his fingers as he clutched his jacket and fell to the ground.

*****

When I wasn't running the streets, I spent a lot of time alone. Having four sisters and two brothers, mostly all crammed into our little row house, that might seem hard, but most of them were out running too which left space for me. Along with drawing and dreaming, I read a lot which led to more drawing and dreaming. I liked drawing cars and superheroes and hoped to one day drive or fly right the hell out of there. But then, books were my main escapee...at first.

My eldest sister Sherry and the next eldest Cathy gave me lots of attention which I craved. One way they did that was to read to me, and before long, I learned to read to myself. We had some ragged Dick and Jane books, The Little Engine That Could and stuff like that. More interesting was the small bookcase right by the front door. (There was also a little umbrella stand which usually didn't hold any umbrellas but always had a baseball bat handy. Just in case.) Along with a beat-up Encyclopedia, there was a well-thumbed dictionary, an atlas, a book of saints and, best of all, a book of mythology! Hercules, Poseidon, Jason and The Argonauts and much more. Sure, the comic books mom pinched for me were great but nothing as awesome as Daedalus building wings for his son Icarus. What a dad!

The comics came from Kelly's Corner, a huge supermarket/ramshackle mall that existed in an old trolley barn on Kensington Ave. at, I think, Sargent St. A dumpy and cool place. Not only did mom bring me comics, she encouraged all of us to read and bought us home coloring books and crayons, paint by number kits and, before he got put away, Joey and me both got nice paint sets for Christmas. Mom also brought home special items she knew I liked. In a corner of the old Penn Fruit, at Frankford and Allegheny Aves, there was a shopping cart full of busted up canned goods, some without labels but most just dented up like some drunk's car. All were priced for pennies and mom always checked out the goods there.

Once mom came home and after unloading packages of meat from her carpetbag purse, she dug deep into one of the fat bags of groceries. After some crinkling and crunching of the brown paper bag, mom pulled out a big can of Campbell's Pork and Beans! Knowing that I thought beans to be probably the finest food in the whole world, she said, "Here, I got these just for you.” In black ink on top of the can, I could just make out that someone had written, "6 ¢". Cradling the can to my chest, like a long lost puppy, I thought, I got the best mom ever!

Along with Sherry, Cathy, Joey and me, my sisters Chrissy, 3 years older than me, and Joanne, 6 years younger, lived in the house too. Although he sometimes crashed on the couch, my brother Russ, about 10 years older, didn't live with us for reasons I didn't understand. Sherry and Russ had a different dad, sure, but Sherry was there and Cathy had a, uh, different, different dad than all of us. And, if you heard my sister Chrissy tell it, Joanne had yet a different, different, different dad but Joanne and me don't believe it. Not that it matters to me. I don't have any half brothers or half sisters, we're all just family, that's all.

Joey started getting put away when he was twelve. Well, if you count various hospital stays, including a long one for rheumatic fever, even before that. Even though I was usually part of his various schemes, Joey was always seen as a bigger problem than me. He showed his hurt more than me, I guess. I remember him sitting alone in the upstairs hallway, rocking and banging the back of his head against the wall over and over. Maybe now, they'd say he was on the spectrum, but back then he was mainly on mom's nerves. Anyway, he got put in reform school or wherever and a hole was torn in my life.

Still, none of what happened to Joey for "being bad" did anything to make me want to be "good" –– far from it.

*****

While it may not show now, I did pretty good in school. Because I could read and write while others were still learning the alphabet, I had a jump over most my classmates. Saint Joan of Arc, at Frankford and Atlantic, was my first school but after my father left, we were transferred to Webster a public school at Frankford and Ontario. While there, I had two wonderful teachers who made a big impact on me. My reading/English teacher, Mrs. Blumberg, really took an interest in me. She would talk to me after class, just asking me how I was doing, what I thought about various readings and things like that. It was then, she would give me presents like a peso from a trip to Mexico and a colorful serape for mom too. Mrs. Blumberg also gave me a warm hug now and again which always broke my heart. I was about twelve years old.

At the same time, there was Ms. Young my art teacher. Very tall with long black hair parted in the middle, Ms. Young was what I would now call the bohemian type. Then, I just thought she was cool. She loved my artwork and gave me the attention and positive reinforcement not always available at home. She actually came to my house on some weekends, picked me up and took me to museums. We saw a Van Gogh exhibit, a Dada show and much more. Ms. Young would ask my opinions about what we were seeing and share hers as well. She also entered me into various contests and drove me to those exhibits too. Looking back, I think she and Mrs. Blumberg knew I was having trouble at home and did what they could to love me in their own ways. And looking how things turned out, people might believe they didn't have too much of a positive effect on me, but that's not true. The confidence they gave me, regarding my own writing and artwork, serve me well to this day. My story wouldn't be complete without mentioning these two beloved teachers.

Every time a teacher asked the class a question, my hand shot up. Once, after class, Ms. Young asked me to not put my hand up every time. Confused, I told her I put my hand up because I knew the answer. She said, "I know you have the answer, you're very smart Thomas but...give the other kids a chance." I felt hurt. (I thought I really did have all the answers.)

One kid I didn't want to give a chance was Harry. Taller than me with the kind of frizzy brown hair where you could just tell he was gonna go bald someday. Anyway, along with others, he started calling me names like "Book" and "Professor" and trying to turn people against me too. One day, he copied one of my ideas in art class and ran to show Ms. Young before me. After school, I said something to him about it. He pushed his face right up to mine, laughed and called me a crybaby. He looked surprised when the first punch hit his face and more followed. At the time, I weighed about a hundred pounds so thankfully he didn't really get hurt. But it was enough to stop him picking on me, and next thing you know, he's following me around like a lost puppy, trying into be my friend. A lesson learned for him and me. Down boy!

Before I finished at Webster, a teacher, Mr. Rubin, sent my mom a note saying they wanted to put me in advanced placement at Master's. First though, I had to get my behavior grades up. Sadly, neither ever happened.

Like my brother Joey, other kids started disappearing from the neighborhood. It was like they got snatched by aliens or something. I mean, one day they were there and the next they were gone. Buddy, Jerry, Johnny, Ronnie Googs and the list went on. Most of the time I didn't think about it but like the monster in our darkened basement, or the one in my bedroom closet or under my bed, it was always there.

After Webster, I went to school at Jones junior high in Port Richmond. Well, I went some of the time anyway. By then, I was huffing solvents, toluol, and bumming school a lot.

We called it pleather. Just cloth covered on one side in brown stinky plastic to look like leather. Masland DuraLeather was a couple blocks down the street from our house, right next to the railroad. It was just one of many plants and factories, in our neighborhood, that belched foul smoke into the air and oozed chemicals onto the streets. At the front of the building, in a yard full of 55-gallon barrels, was a loading dock and a large dumpster filled with all kinds of trash. Dirty coffee cups, bread crusts, empty five-gallon cans and, best of all...scraps of pleather! We climbed into the dumpster and grabbed pieces of DuraLeather to fashion into belts, pocket books and other junk we wouldn't be able to sell. It was fun!

It didn't take long for someone to discover that among all sorts of foul chemicals, some of the barrels held toluol, a solvent that would produce "dreams" if you breathed enough in. So, we'd tip the battles and fill pint bottles to the top with "T" which we huffed from soaked rags. Some many kids huffed that there actually was a hustle of selling toluol at five bucks a pint or a quarter a dip for a soaked rag. It seems so crazy to me now but my whole crowd huffed for a couple years in our early teens. Between that and the drugs and all the hits to the head, it's a miracle that I can still tie my own shoes! Bumming school and hiding in the sumacs by the railroad, we huffed and dreamed until our rags and dreams all ran dry.

It was a short hop from breaking into Masland's for toluol and pleather to breaking into other factories for knit sweaters and anything else we could hustle for much-needed cash. We also started breaking open the boxcars that rumbled down the many railroads that cut through the neighborhood. I got arrested for that and picked up for bumming school too. Next thing I knew, I was on probation, just like a lot of my friends were. Still, Mom would always pick me up at the police station and drag me to court too. Until she didn't.

***

It should've been pouring down rain but instead the sun was shining stupidly as if my little world wasn't falling apart. It was April Fool's day, 1974, I was fourteen years old and heading up the Gabes, so, I guess the joke was on me. As the Sheriffs car turned up the tree-lined driveway, I could hear the gravel spray under the tires and I saw close-up the huge red-brick building that had been looming in the distance for quite a while by then: Saint Gabriel's Hall, that's a reform school in Eastern Pennsylvania run by Christian brothers where they put kids like me. Although I didn't consider myself a bad kid, other people kept telling me I was, so, there it is. To tell the truth, it was my mom's fault that I got put there because she told the judge that she couldn't handle me anymore but that's another story. About two years earlier, mom had put my older brother Joey there too, and I remember he had some problems with at least one of the older boys there picking on him. As the car pulled closer to the front of the massive building, it was my guess that things probably weren't going to be too good for me there. Either way, I wasn't even sure where the hell I was, map-wise, so making a run for it didn't seem like a good plan right off. Welcome to the Gabes kid.

I swallowed hard as I looked through squinted eyes out of the car's window and tried to get my bearings. Man, there were trees galore, not like my neighborhood, Kensington, back in Philadelphia where I grew up. All we had were factories, railroads, bust-out bars and street-after-street of red-brick row houses everywhere. Looking past the driveway, leading up to the entrance, I could see mowed grass in almost every direction with various buildings scattered about and there was even a fenced-in swimming pool off to one side of the road. Then the car pulled into a circular driveway, stopped and one of the sheriffs got out, opened my door, then reached in and took the handcuffs off. My hands were cold from the lack of circulation so I tried to rub the blood back into my skinny wrists as I got out of the car. On a morning like this, back in Kensington, the looms would be banging away in the factories, trucks would be rumbling down the tight streets and kids' voices would be bouncing off every wall as we hustled off to school... but not that morning—up the Gabes everything was quiet and still. This might sound crazy but even the birds' chirping seemed hushed and far away, as if they were afraid to make too much noise as they went about their business. The whole thing had me shook-up—I mean, getting put away had me shook-up most of all, but the sun and the trees and all the quiet wasn't doing me any good either. Despite that, I put on my toughest face as the sheriffs led me up the stairs and through the doors into a dim corridor where they delivered me to Brother Somebody, a huge preying-mantis in clerical-garb, whose day I was apparently ruining.

"Come on, come on, let's go," he said as he dug a couple of bony fingers into my arm and dragged me down the corridor. And, down I went.

I can't say that I remember exactly what happened next. I do remember being taken to an office where papers were produced, shuffled, signed and, I guess, filed. Every now and

then, somebody looked over at me and said some words that I couldn't make out but the tone seemed bad—what the fuck. At some point, I think I got a shower, and I was handed off to one Brother Barry who was the prefect of Omicron fraternity where I would be living for what turned out to be the next fourteen months. Brother Barry was a short plump man with a little boy's haircut and a face that looked both dry and waxy at the same time, like if you peeled the skin off a potato and then toweled it off. And while he was not a physically imposing man, he was the authority over us kids and he sometimes made things very unpleasant for us there on Omicron. You see, back then, corporal punishment was still the preferred means of discipline and we got plenty of that up the Gabes. In addition to being made to stand silent and motionless "on line" for hours a day, occasionally for weeks at a time, there also were "bendos" where we were forced to bend over a desk while our asses were paddled with a variety of implements. Exactly how hard you got hit and with what depended on who was doing the hitting. Some prefects would use a ruler, others a ping-pong paddle and there were even some bastards who would have their paddles customized for maximum damage. Like this one creep, Brother Arnold, a fat-assed, stogie-smoking sadist who, in addition to swinging a heavy paddle, let everybody know that the pattern of holes he had drilled into it was so there would be less air-resistance which could slow the paddle down and soften the blows. Lord knows, we can't have that. Thankfully, Brother Barry wasn't the hardest-hitting prefect I encountered there. Still, it was pretty icky having to "assume the position" for him because whatever it was that he lacked in strength, he made up for in creepiness. Of course, it has to be said, that if beating and humiliating children made them act any better, most of us wouldn't have been up the Gabes in the first place—for us it was just more of the same. Even the times when we were able to avoid getting beat, if only for a while, the threat of it hung in the air, thick and toxic as the stink of a cheap cigar.

I have to tell you, it wasn't only the staff that we had to worry about; the kids could be pretty hard on each other too. There was a lot of stealing, physical violence and even sexual assaults among the kids there—it could be horrible at times. Yet, on a day-to-day basis, the biggest problem was one of bullying. You know, young boys can be merciless at times and, as much as it was needed, too often, there wasn't much mercy to be found up the Gabes. Intimidation, name-calling and other forms of verbal harassment were most prevalent, but there were a lot of so-called practical jokes played on people too. Someone might mess up your bed which could get you into trouble with Brother Barry, or somebody might hide your glasses before you went to school, or maybe they' d smear peanut-butter or something in your coat-pocket when you weren't around. But the meanest shit of all was when some kid would be brushing his teeth and everyone would start laughing at him because some bully had "chump-rubbed" his toothbrush on their dick when he was sleeping. Someone might actually comb their pubes with your comb, piss in your shampoo or other creepy shit like that. Now I think that the humiliating things that the kids suffered at the hands of each other were really just a continuation of the humiliations that we all suffered at the hands of the staff there. I mean, think about it, Christian brothers paddling the asses of vulnerable young boys on a regular basis. What the fuck was that supposed to be, one of the perks that came with the job? And whether it was the staff administering the punishment directly or allowing some kid to do it by proxy, there were usually some sexual overtones to it. . . and that's the big fear right? Nobody wants to get raped.

After I was shown my bunk, the rest of the fraternity, and then "squared away," the other kids started filtering in from school for the lunch-break. As soon as Brother Barry disappeared some of them started in on me: "Hey, I didn't know they was putting girls up here now,” some big kid with a missing front tooth said. Then he added, "Hey baby what's your name?"

The other kids laughed, I didn't say anything at first, so, it went on from there with different kids calling me names, asking smart-assed questions and some were even threatening me. Even though I had put on my toughest face, my heart felt like it was going to beat its way right out of my chest and run straight back to Kensington without me. After some very long minutes, Brother Barry reappeared, then organized us into two lines. We were marched down some stairs, through a couple hallways, then down some more stairs and finally into a large dining-room where there were other kids already seated on both sides of these long wooden tables. I just followed the kid in front of me, picked up a tray, some silverware, and a cup, then jostled my way through the chow-line accepting every bit of food that was offered up. I have to say that, although I don't remember exactly what was on the menu that first day, I do remember, that in spite of everything, I was pretty hungry. When I walked back to the dining-room, I spotted an empty seat and sat down next to this heavy-set, pimply kid whose name turned out to be Chris Rivera.

Brother Barry had again slipped off somewhere and no sooner than I started to butter my bread that Chris turned in my direction and announced to the whole table: "Hey, I'm starving; maybe the new girl will give me her tray."

For a moment or two, I tried to pretend that I didn't know he was talking to me, but when the other kids started to chime in, I knew I couldn't fake it anymore. I tried to give it right back to him but I felt all short of breath and all I could come up with was shit like, "You're a girl, not me" and "you ain’t taking nothing from me." You know, shit a scared kid might say.

"You little pussy," he said with his face, red and greasy, just inches from mine, "wait till we get back on the frat 'cause I got something for you."

I tried to talk but my mouth felt like it was full of cotton. Then, as the hoots and howls started to get louder, Chris stared me right in the eye and reached over and grabbed the food right off my tray. Before I could even think about it, I swung my fork down hard and stabbed right into the meaty part of his hand, between his thumb and index finger. Then I jumped to my feet and, both trying to look hard and hold back the tears at the same time, I started pointing the fork around at everybody, telling them: "None of you motherfuckers is going to do anything to me."

Just then, someone hissed, "Brother Barry, Brother Barry,” so I sat back down as the rest of the kids moved food around their trays like nothing was happening. Meanwhile, a shook-up Chris pressed a paper-napkin, with a few small drops of blood blossoming through, against his hand as he told me, again and again: "I was only playing, I was only playing."

Later, back on the frat, some of the kids approached me. "Damn, boy, you crazy,” said a husky black kid, shaking his head back-and-forth.

"Aint nobody trying to take anything off your plate, huh?" a red-haired fire-plug of a kid told me with a grin on his face. Then, one after another, the kids started introducing themselves to me, "Yo, they call me Taboo" said the husky black kid.

"Hey, I'm Carson, what's up?" said another kid.

"My name's Sam Virgillini—everybody calls me Virg," a short Italian kid said as he stuck his hand out in my direction.

And so it went, with kid-after-kid shaking my hand and giving me their hand. Finally, the big knot that was in my stomach all day started to loosen up... a little.

"Hey, does anyone got a smoke?" I asked hoping.

"Yeah, take one of mine" this athletic-looking kid, named Stanbaugh, told me as he shook a Marlboro from his pack—it looked like I was in. But, for Chris, things didn't look as good.

“Whoo, that boy stuck a fork right in your fat-ass,” Taboo said. Then added, “You better watch somebody don't stick something else in you too."

The other kids laughed and then some of them started in on him too. "Damn, Chrissie, it looks like you'll be given your food to the new-guy now,” some chipped-tooth kid sneered.

“Yeah, maybe now you'll get some of that lard off your ass fat-boy,” said another kid who had a fat-ass himself.

As I looked over at Chris' now pale face, I was beginning to figure out that Brother Barry was never going to be around when he was needed.

It turned out that Chris had been getting bullied all along and it looked like he was trying to get the heat off him by putting it right on me. I got to tell you, the poor kid had more names than you could shake a stick at: Chris the crud, Fudd the crud, Pizza-face, fat ass, Pissy Chrissie and, given the situation, just plain old Chrissie did the trick too. In addition to being fat and having pimples and being named Chris, he also pissed the bed on occasion and, this is crazy, he actually played the flute! Dude, you can't play the flute in reform-school. The drums or the guitar, yeah, but you're just asking for trouble with the flute. Then, with nothing to show for it but a couple of fork-holes in the meat of his hand, Chris was back right where he would remain for his whole time up the Gabes: down at the bottom of the pile.

That night, after lights-out in the dorm where we all slept, I pulled the covers over my head and cried as quietly as I could. I cried because I was up the Gabes and I cried because my mom had put me there and I cried, most of all, because I was fourteen years old and I was afraid. A few days later, I put shaving-cream in Chris' sneakers.

***

If you would like to send Tom a note, you can write to him at:

Smart Communications/PA DOC

Thomas Schilk #AS0255

SCI Phoenix

PO Box 33028

St Petersburg, Florida 33733