The Fight for Non-Police Responses to Mental Health Emergencies Continues

October 26, 2020 is a day that will remain etched on our hearts. Still reeling from the murder of George Floyd and the nationwide uprisings thereafter, the ugly and traumatic cloud of police violence visited our neighborhood.

Walter Wallace Jr., was a son, a twin, a newlywed, and soon-to-be father. He also struggled with his mental health. On that fateful day, his family called 911 for help because he was having an episode. Instead of helping, Philadelphia police officers murdered him in front of his mother who was begging for his life.

Walter Wallace’s death shook our West Philly community to the core. While mental illness remains deeply stigmatized in our society, it is more likely than not that someone you know and love has mental health struggles. In him, we saw our brothers, our cousins, our friends, our neighbors, or even ourselves. Walter Wallace Jr and his family deserved so much better. Police simply have no business responding to mental health crises. It is this belief that brought Amistad Law Project and local social workers and other clinicians together to form the Treatment Not Trauma Coalition. We were determined that what happened to the Wallace family should never, ever happen to another Philadelphia family.

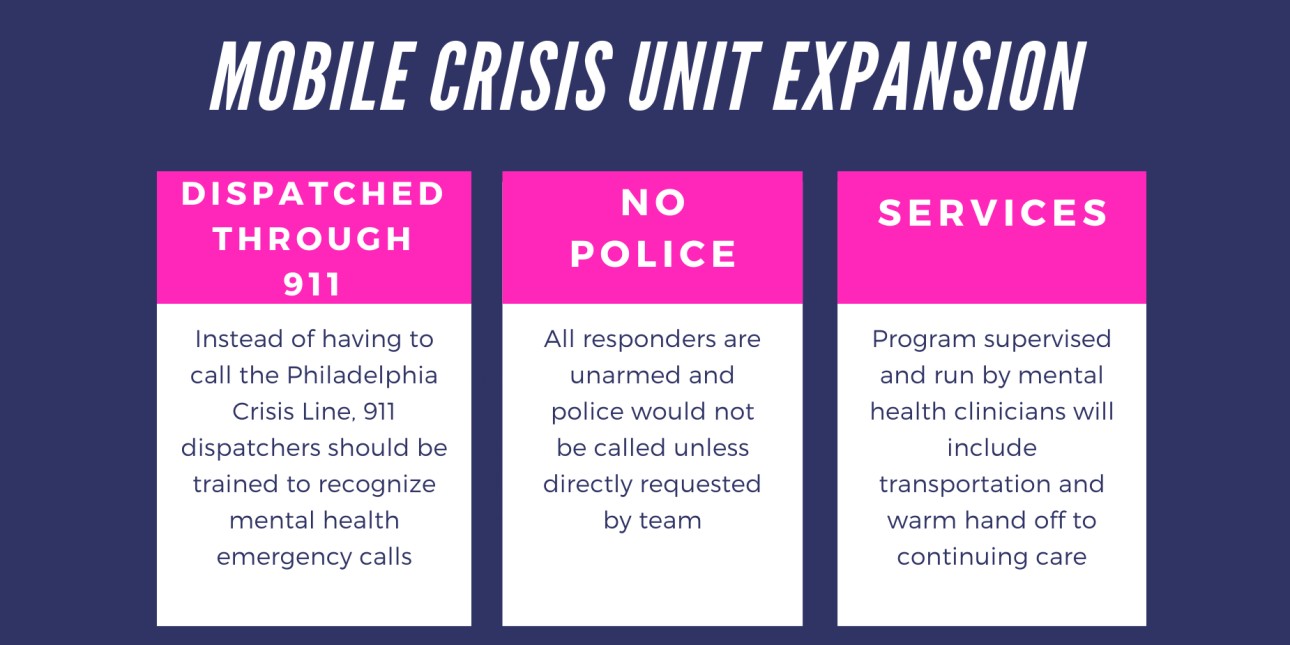

Through a vibrant and strategic campaign in the Spring of 2020, Amistad Law Project and the Treatment Not Trauma coalition were able to help the city take a small step in the right direction. We waged a successful campaign to secure $7.7 million in funding for non- police mobile crisis teams in Philly and took some mental health calls out of the hands of the police. While this is a step in the right direction it’s not enough to fully serve the city and ensure that all mental health emergencies are answered by unarmed mental health professionals.

Furthermore much of the City of Philadelphia’s answer to demands for change was to offer disappointing and potentially harmful reforms--increased police funding for tasers and funding for a ‘co-responders’ program that would pair a police officer with a behavioral health clinician to respond to some mental health calls. The police co-responder program, also known as Crisis Intervention Response Teams or CIRT, has been heralded by the city as a step in the right direction.

We disagree. We want to see the mobile crisis teams we helped to win funding for in the Spring expanded and the co-responder program closed down.

The National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis, published by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), asserts that best practice for mental health crisis response is mobile crisis teams that respond without law enforcement accompaniment. Throughout the guidelines document, SAMHSA is critical of cities defaulting to police operating as community-based mental health crisis response teams.

What CIRT actually represents is a further entrenchment of law enforcement in a place that law enforcement has no business being in, for the sake of maintaining the status quo.The implication behind a continuum of care that includes a co-responder model is that there are some people experiencing mental health crises who are violent; we reject this framing. We have seen time and time again what happens when Black and brown people are in crisis—we are called violent and our murders by law enforcement are deemed justified. This is why we cannot allow a co-responder program to continue in Philadelphia. Cops can’t heal. We believe that the City can and should do better for its residents by not continuing to invest in a police response to mental health crises.

What we have been seeing across the country in cities that have both a police and non-police mental health response, such as the STAR program in Denver, is that even though non-police mental health responder program is having excellent results, it is undermined by having the overwhelming number calls that could be going to the non-police response instead being routed to the co-responder. “During the initial six-month period, police received 95,000 calls, 2,500 of which fell into the STAR’s scope of operation. However, only 743 calls were actually routed to STAR - representing just under 3% of all police calls.” By comparison, the CAHOOTS program in Oregon responds to 17% of all calls.

In order for community mobile crisis units to succeed, we must allow them to actually be the first responders responding to ALL mental health calls. The current proposed expansion of mobile crisis teams will save lives if it is fully supported and done right.

The fact of the matter is that Philadelphia and many cities around the country have systematically defunded mental health services while allowing police budgets to balloon to obscene amounts. This isn’t just about who shows up in an emergency--this is about the persistent underfunding of basic mental health care that people need before there is a crisis.

Amistad Law Project and the Treatment Not Trauma Coalition are working to ensure that mobile crisis expansion will be what Philadelphia needs it to be, to reduce the presence of armed law enforcement in the various crises our neighborhoods may face, and to make sure people with lived experiences have a seat at the table. We will continue to fight until our communities have all the resources we need to be healthy, safe, and strong.