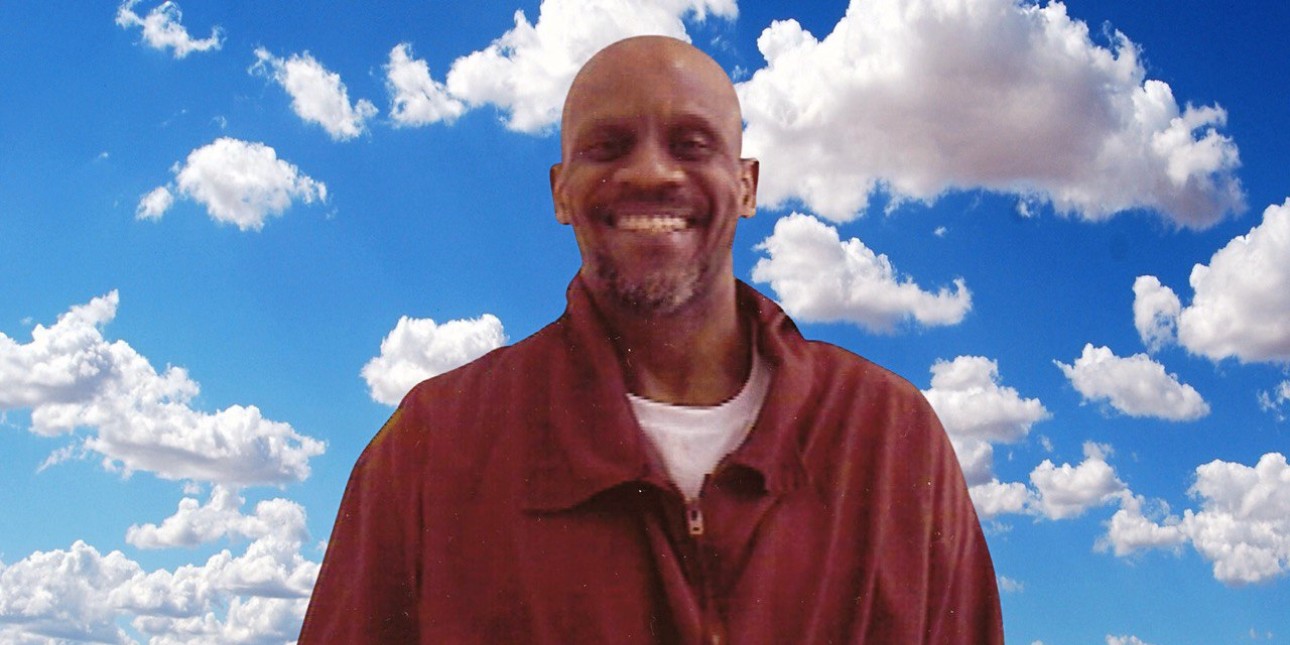

You Cannot Contain Those Who Do Not Submit: Remembering David ‘Dawud’ Lee

A tribute by Sean Damon.

“At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.” ― Ernesto "Che" Guevara

The call came at 8 AM and I thought it was Dawud. I talk with many people in prison, but very few people call me that early, and certainly no one from SCI-Coal Township. The next day he was to be up for a vote at the Board of Pardons, and as I saw the number flash across my phone, I thought he must be calling to talk about the pending hearing. I listened to the prerecorded message announcing that I was receiving a call from a state prison and my hands did their usual dance, pulling the phone from my ear so I could look at the screen and punch ‘1’ on the keypad to accept. My friend Phillip Ocampo’s voice came on the line and he didn’t have to say anything. His tone, the time, and months of watching Dawud’s health fall apart told me everything I needed to know. My voice was calm and centered on the phone, but inside I crumbled.

Dawud’s health had been disastrous in recent months. In August of last year, while attending a friends and family banquet at SCI-Coal Township, my wife and I watched him walk to our table from across the room and arrive needing to catch his breath. A number of us from Amistad Law Project and Abolitionist Law Center had sprung into action, doing everything in our power to advocate for outside testing and serious attention to his worsening condition. Even with several lawyers in the mix, the prison health bureaucracy did not get him outside testing until the crisis accelerated. Still, in recent months, he had seemed to stabilize. At the end of the last year, he was often winded when we spoke on the phone. However, since he was confined to the infirmary and was receiving supplemental oxygen when walking, he said he was doing much better. A week before his death, we sat with him while he spoke passionately with us for several hours. The truth is that the mind and the heart have a way of trying to make a deal with unpleasant realities. At that moment, as his health fell apart and as we got him listed for reconsideration at the Board of Pardons, I think many of us wanted to believe that if we got him home there was something that could be done: specialists to visit, tests to run, and treatments that could help him find a new stable normal. Perhaps he would be physically diminished, but he could live. The reality was that the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections and the Board of Pardons had wrecked his health.

He had a disease that caused inflammation and clumps of white blood cells to form in various parts of his body, particularly his lungs. The disease was mostly untreated because of Dawud’s incarceration. He did everything he could to mitigate the harm of his condition. He stayed away from foods he believed would exacerbate it, like dairy, and in the many years I had known him, he put a premium on exercise to retain his strength. However, in terms of the care many of us could squeaky wheel for ourselves out here (even in the horrific context of the for-profit American healthcare system), he had none of it. No regular visits to a pulmonologist, no regular CT scans, and hardly any treatment that could arrest the flare-ups that occurred on a fairly regular basis. With each flare-up, more scar tissue formed in his lungs. Eventually, as his lungs were compromised, his heart began to fail. It’s true much of this could have been mitigated, delayed, and possibly even arrested, but not while he was in prison. In prison, you just hope that you don’t get sick.

The prison may have wrecked Dawud’s physical form, but it never did touch his spirit. While the constriction of prison life pressed in around him, Dawud had places to roam inside of himself. He had an expansive interiority that he drew from like a deep well. Through this rich inner life, he was able to draw on an abundance of emotional strength to mentor people, especially young people, and show them love. He did this on a scale that would be hard for many of us to grasp, given how much effort it takes to build genuine relationships and patiently teach others. And he did it with a broad section of humanity, both inside and outside of prison walls. At his funeral, Kris Henderson of Amistad Law Project spoke about the hundreds of people he mentored over the years, and drawing back the lens a bit, the thousands of people those people were able to teach in turn.

He did this even when the crabs in the barrel mentality surrounding him might encourage otherwise. It is not that he wouldn’t get upset when someone betrayed his trust or disappointed him; it's that while some of us might be ‘once bitten twice shy’ after getting burned, Dawud wouldn’t hesitate to reach out to the next person, and the next, and the next. Counterposed exactly to the crabs in the barrel mentality that he despised, he saw his liberation as directly bound up in others. He didn’t embody some selfless state of love, but he loved himself profoundly and that self-love then extended to the larger collectivity that needed to be developed if he or any of us were to be liberated. Dawud lived the maxims ‘each one teach one’ and ‘no one is free while others are oppressed’ in such a serious way that he might have been a living incarnation of them, or at least the closest I’ve ever seen.

He was lucky to be mentored by incarcerated revolutionaries, such as Russell ‘Maroon’ Shoatz, and to exchange ideas with other incarcerated comrades such as Robert ‘Saleem’ Holbrook, Reuben Jones, and John Thompson who took the development of their intellect and consciousness seriously. But he was also largely self-taught, or as some like to say in theory-heavy radical circles, an ‘organic intellectual.’ Many of us have heard him tell the story of how, in the lineage of Malcolm X, he taught himself to read using a dictionary because he was so hungry to read Black liberatory thought. As he would tell it, when he opened the door to new ways of seeing the world and being in it, the criminal lifestyle he had wasted his youth on was completely eclipsed. Through consciousness-raising sessions with other incarcerated people, he got a glimpse of how the world actually operates, and he pursued that knowledge relentlessly. From that point on, he saw the criminal lifeways he had once partaken in as pointless games that would lead nowhere and harm his community, those he loved, and ultimately himself. Besides, he would say they were completely beneath a dignified human being who was conscious, aware, and had their eyes on the prize. He despised those games and many of the games that came along with prison politics and outside politics too. He would often laugh at the idiocy of some of the short-sighted schemes that people would cook up to jockey for power, and he would calmly and patiently attempt to explain how those schemes would unravel. If people wouldn't listen, he would keep it moving and let them fall on their faces so they could learn for themselves.

He had other ways of teaching people too. He was a writer who wrote short missives on topics ranging from patriarchy to conceptions of time to death by incarceration, and while the subjects were often heady, his writing was as straightforward as he could make it, given the topics. For Dawud, there were always multiple audiences. There were the movement folks familiar with more advanced concepts and frameworks for understanding society, and the new kid on his cell block from North Philly, who was deep in the game and who he was trying to reach. He wrote in an accessible style, which is to say he wrote for poor people who are mostly shut out of getting a quality education because of under-resourced public schools and the many pressures of poverty that derail your life, including your schooling.

While our world—steeped in racism, class rule, patriarchy, and all the myriad forms of oppression—tears communities apart, Dawud built them. I have met few community builders as talented as him in my entire life. He stitched together people across worlds: community leaders in the Coal Region, abolitionist organizers in Philadelphia, educators from across the country, formerly incarcerated people from every walk of life. Dawud built a very particular network, and it was not shallow. He was able to hold very deep relationships with many people and all of those people felt like they were someone special to him—because they were. He valued people. He recognized their unique contributions and gifts. Like a patient gardener, he nurtured them and the possibilities they contained.

He was also my friend. My wife and I mentioned him in our wedding program as someone we had hoped could have been there to celebrate the day with us. I spoke with him almost every week. When I was traveling, I would always pick up his calls so I could smuggle him a view of far-off places through my narration. I remember standing on a street corner in Hanoi and describing to him the torrent of motorbikes nearly running into each other that streamed down the streets. We talked about the work we would all do together when he got home, and it had been our intention collectively that he would have a leadership role at Amistad Law Project. We joked about how we would have a reclining chair for him in the office so he could really channel his revolutionary pop pop vibes, and how we'd stock the flavored water he enjoyed that Kris Henderson liked to tease him about.

Mostly in the last few years, our conversations had alternated between our usual lighthearted banter and the serious business of trying to get him out of prison. In 2022 after years of work, Dawud secured the recommendation of his prison superintendent and the Department of Corrections in his efforts to have his sentence commuted so he could come home. We worked to advocate with various people including then-Attorney General Shapiro who is now the Governor. In the end, he got the support of everyone but two Republicans who sit on the Board, who were initially appointed by Democratic Governor Tom Wolf: Psychiatrist John Williams and Corrections Expert Harris Gubernick. As Audrey Pan, one of our star interns at Amistad Law Project in 2022 pointed out, “The Board of Pardons is just five dictators.” Without a doubt, two of those dictators condemned our friend to die in prison.

Dawud would want us to continue to try to wrench people free from the broken-by-design machinery that is The Board of Pardons. And, no doubt, we will. But we will talk about the cruel lottery that it is and the people who make it immeasurably worse. The truth is that Dawud’s condition got much worse after a flare-up of his disease in 2023. If he had been approved in 2022 and came home later that year, there is a very good chance he could have received treatment that would have helped to mitigate that disastrous flare-up. At the very least he could have had the dignity of free life. Towards the end of his life, he just wanted to take a bath, and he often talked about the things he’d like to eat, both because they would be delicious and would improve his health. The version of reality where he has some good years left was stolen from him and from all those who love him. We will never forget it.

I miss Dawud. I had a lot yet to learn from him, but what he taught me has been invaluable. I will work for the rest of my life to put those lessons into practice: to tend to the emotional expanse within ourselves and make it a place from which we draw strength, bravery, and love. To refuse to submit to the power structure, and build the biggest coalition we can to surround it and surpass it. To, above all, live a dignified life, no matter what hardships you encounter. One day, when we win, as people stream past prison gates, I will see his face in the crowd. Then just as suddenly, it will vanish. He is free and he always was. They never held his spirit captive and now he lives on in us.