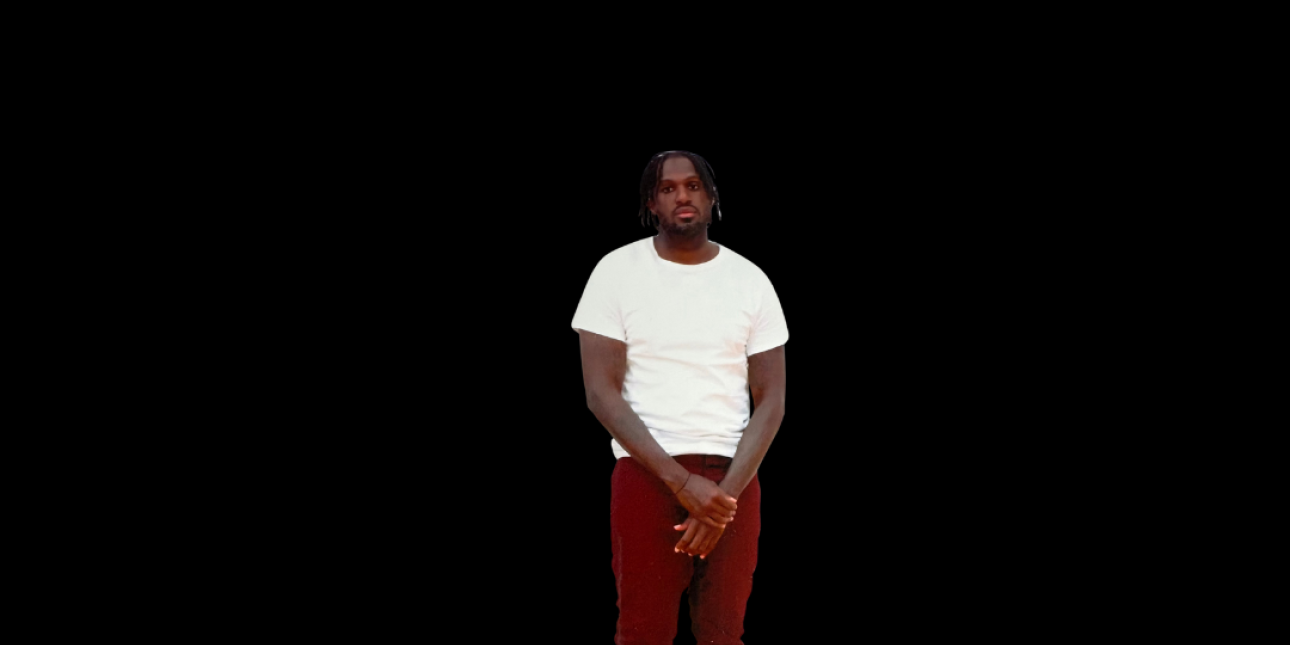

Qu'eed Batts: The Transformative Justice Practitioner

Qu'eed Batts is the co-author of Weology: Transformative Justice in Practice and a facilitator of Dare 2 Care, a transformative justice program for men behind prison walls. He was tried as an adult at the age of 14 and sentenced to Death By Incarceration. Batts challenged that sentence as unconstitutional, and his case was picked up by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, leading to a major victory for children sentenced to mandatory DBI. Despite that victory for child lifers broadly, he was handed a virtual life sentence of 50 years to life at his re-sentencing. He lives and works at SCI Somerset.

I grew up in the projects. My mom and I lived on the 5th floor of a building in Elizabeth, New Jersey. In those types of communities, everyone looked out for everyone else’s kids. One day when I was five years old, I was playing in front of the building, and my mom, who was 18 at the time, told someone to keep an eye on me for a minute while she went inside. I wandered off around the corner, and my mom’s aunt, my great aunt, saw me around the corner and was like, “I’m gonna teach your mom a lesson.” Then she took me.

I didn’t think anything of it because it wasn’t unusual for me to be with my aunts and other extended family. For three days, she kept me in her house while the entire community, including the police and city officials, were out looking for me. My aunt didn’t mistreat me when she kept me in her house, but she did kidnap me.

When I was finally found, the state took me away from my mom and put me in foster care. Nothing about the situation was my mom’s fault, but that was their response to an 18-year-old woman in the projects who had me when she was 13.

Once I was in the system, it was really hard to get out. They moved me around all the time. Sometimes I would be with foster families in New Jersey. Other times, someone in my family would foster me, like the time I lived with my uncle for about a year and when I lived with my grandfather in both New Jersey and South Carolina. At one point, I had to live in a homeless shelter for kids in Trenton, New Jersey. During my stays in foster homes, I was moved all over Jersey, from Elizabeth to Passaic, Hillside, Newark, Irvington, East Orange, Roselle, and Union. All told, I was in foster care from the age of 5 until I was 12 years old. There were no consistent people in my life. I didn’t have a single person I could count on. It was just me, and I had to learn how to roll with the punches.

Foster care is basically the same as prison. You're held against your will in a place where you don't want to be. You’re constantly surveilled, jumping through hoops, having new rules imposed on you. When I got to have visits with my mom, they were supervised. The longer I sat behind these prison walls, I couldn’t help but think how my entire life before prison prepared me for my life in prison.

Things in my mom’s house were different when I was finally returned to her. She was partnered to a man who I came to know as my stepdad, and my mom was pregnant with my little brother.

I had finally made it back home with my mother, but we still had a lot to work on. I had met a friend who I looked up to and he was part of a gang, so I joined too. He was a few years older than me, and I was with him almost every day. He looked out for me, so I was attracted to the sense of brotherhood.

At age 12, I was initiated into the gang. Less than two years later, I was charged with the murder of another teenager. If I went through with it, it would reinforce my allegiance to the brotherhood and deepen their commitment to me. So, I took another boy’s life.

I was immediately put in isolation in the Northampton County Prison because they said it was too dangerous for a 14-year-old to be held with adults. They kept me segregated in the county jail until I was 16, when I was sentenced to Life Without Parole, or what I call Death By Incarceration.

You might be wondering why I was charged as an adult if I was only 14 when I committed this crime. Basically, the juvenile system is geared toward rehabilitation, while the adult system is focused on punishment. The state said I couldn’t be appropriately treated in a juvenile facility, so they had a decertification hearing and transferred me to an adult court, where they decided I wasn’t capable of rehabilitation.

It never occurred to me that I could receive what’s essentially a death sentence at such a young age. The county offered me a plea deal, but my lawyer encouraged me to take it to trial because he didn’t think there was a chance they’d put me away for life, even if we lost. He figured they’d sentence me to something like 20-40 years. I didn’t know that, at the time, Pennsylvania sentenced more children to Death By Incarceration than any other state in the country. I joined the ranks of over 500 other kids sentenced to die behind prison walls.

After they sentenced me, they moved me around to different prisons throughout the state, just like they had in foster care. Every time I went to a new facility, though, they put me in the hole because I was still under the age of 18. They let me out for one hour a day to go the yard, and for 30 minutes to shower on Monday, Wednesday, and Fridays. Solitary confinement is usually where they send people for punishment, but they segregate children there in adult prisons because they say it’s too dangerous for us to be out in population with all the grown men. If they don’t think it’s safe for kids to be in an adult prison, they probably shouldn’t send them here in the first place. Whatever the case may be, from the ages of 14 to 18, I spent most of my weeks locked in a cell for 23 hours a day.

I finally got out of the hole for good in 2009 and got my GED that same year. That was a real accomplishment for me because it was the year I was supposed to graduate. Earning my GED was a way of keeping a promise to myself to stay on track, no matter what was thrown at me.

I didn’t know how my life was about to change when I was transferred from SCI Frackville to Coal Township in 2016. At age 25, I was ready to turn the page on my involvement with gang culture. I was in the hole for seven months, and I was having a conversation with an old head about family. I began to explain how close of a relationship I had with my brother, who was 11 or 12 years old at the time, and he asked how it would make me feel if my brother followed in my footsteps. Of course, I said I didn’t want that. Then he asked why I would involve myself in things that I didn’t think would be good for my little brother. It caused me to do some reflecting, and I made a decision then to change my ways. I didn’t say it out loud to anyone, but as I transferred to Coal Township, I was ready to start fresh.

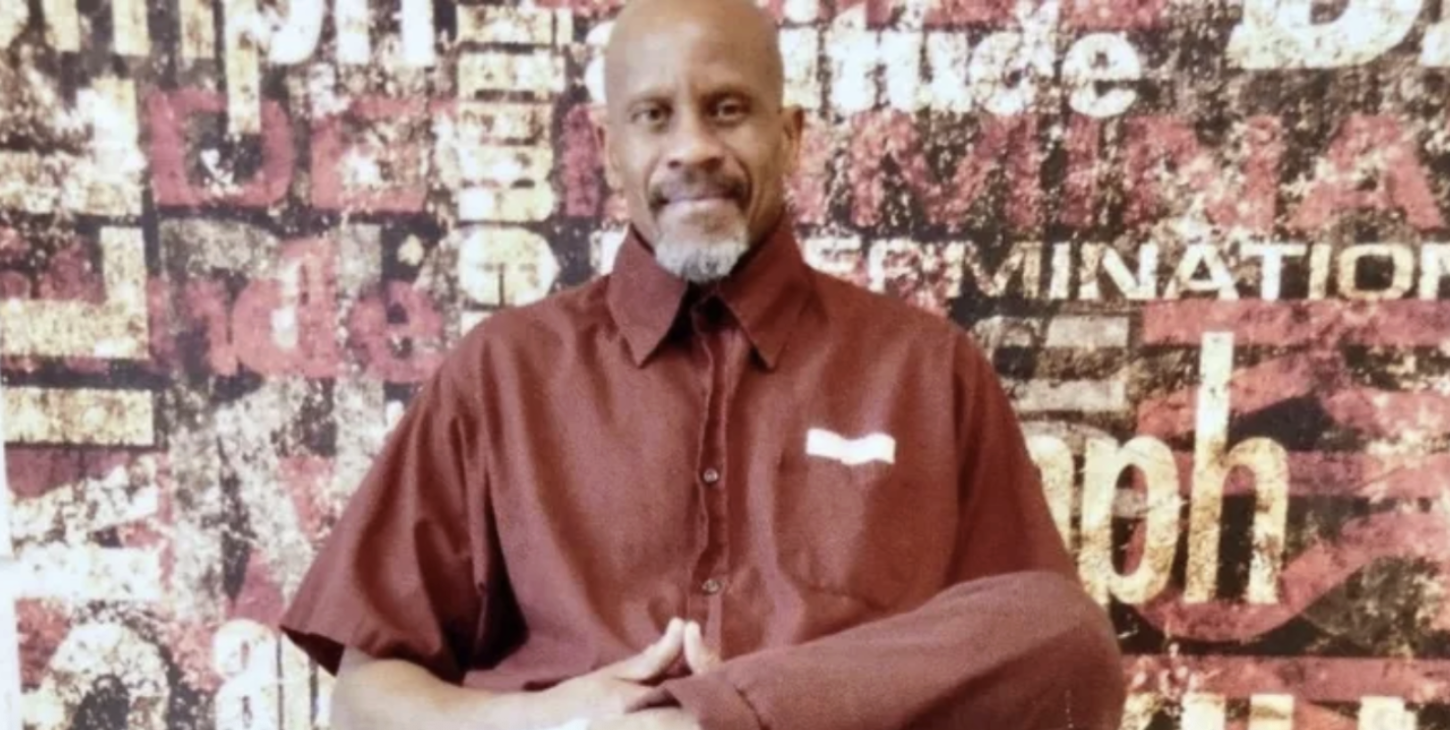

Dawud Lee’s reputation preceded him. When he got to prison in the late 80s, he taught himself to read and devoted himself to understanding the societal ills that led to him and so many of the people he loved getting locked up. From there, he started a program called Dare-2-Care, where guys inside come together to talk about the circumstances that led to us causing harm in our communities so we could take responsibility and begin to work toward repairing that harm.

A friend named BC, which stood for Brian Charles, introduced me to Dawud in the yard when I got to Coal. Dawud asked me where I came from and what I had going on—what my intentions were. I had no political education at the time. I had been deeply involved in gang culture from the age of 12 really up until I met Dawud. But I had made a decision within myself to change, and Dawud must’ve seen potential in me.

He asked if I was done with gang life, and for the first time I said out loud that I was done with it. He was like, “Alright, I’m gonna move you into my cell with me. And from them on, that was my big brother. I didn't know at the time that I was starting a new life, but he had a plan for me.

Initially, he just let me do my thing. I think he wanted to see where my head was at and give me time to adjust to the new environment. He was always reading. He never watched TV during the daytime, always had a book in his hand. He also wrote essays. Eventually, he started asking me to read the stuff he wrote, and then he’d ask what I thought about it. Of course, I had no understanding of a lot of the things he was writing about, so I’d ask questions. That’s how we got on: he asked me to edit the essays he wrote, and then we’d discuss them, and that was the start of my political education.

The first book he gave me was Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. The book is a letter from Ta-Nehisi to his teenage son about what it means to be Black in the United States. I didn’t put it together at the time, but looking back, Dawud was guiding me like a father guides his son. My father went to federal prison when I was 9 years old. Dawud became the first consistent presence in my life. Along with reading and discussing big ideas together, I would just watch him, how he moved, how he went about his day to day. Most of his close friends had been transferred to other prisons at that point, so he spent all of his time reading, writing, and mentoring guys like me.

Dawud started Dare-2-Care right around the time I got to Coal. Roughly 15-20 guys met every week for about an hour and a half. Facing one another in a large circle, we talked about our years growing up, the circumstances that led us here, and how we wanted to change. I was proud to be in the first graduating class in 2017, and then Dawud made me facilitator.

When COVID hit, we were locked down constantly. We were each let out once every three days for a total of 15 minutes to shower and use the phone. Other than that, we were couped up in our cells. But the work never stopped for Dawud. We started writing a book together called Weology: Transformative Justice in Practice. Dawud invited two other guys named JaJa and Nyako to join us. The four of us contributed essays, conducted interviews with one another, and I also served as the editor for everyone else.

With Weology, we wanted to highlight how transformative justice works in the heart of the prison industry—how transformation takes place, and how harm is prevented. It served as a way to show how we help each other heal even after harm has taken place without including the state.

In the introduction, we say, “Ultimately, transformative Justice is practice. It’s brotherhood and sisterhood, it’s fatherhood and motherhood — it’s family. It’s community, it’s culture, it’s healing... It’s having the courage to attempt to address the ills of this complex society with love, empathy, and compassion. And for those of us who are trapped in these cages immersed in violence and pain, it’s a path to redemption.”

In our work together, writing and teaching transformative justice, Dawud taught me that just because I had done harm in our community, it did not mean that I should be written off. He also taught me that all of our struggles are intertwined. Our fight for freedom from these cages is connected to the fight against white supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism, and all other systems of oppression. It’s not enough to fight for our own freedom—we have to fight for the collective.

From the day Dawud moved me into his cell, I knew he was sick. He coughed a lot and told me he had sarcoidosis, a disease that affected his lungs. But the bigger problem was a heart condition that had been misdiagnosed. In late 2023, he started walking very slowly and breathing differently. He would be completely out of breath walking up one flight of stairs.

I was briefly transferred in October of that year for a court date, and as soon as I got back in December, I knew it was serious. Dawud had started using a wheelchair and living in the infirmary full time. He would come up to visit us on the block, though, and that’s when he told me he needed a pusher. I immediately went to one of the deputies and told him, “Hey, I want to quit my job in the barber shop and become Dawud’s pusher.” He said that was no problem, so I got to devote all my time to caring for Dawud in whatever ways he needed.

His spirits were still high. I’d get a call from the block to go pick him up, and I’d roll him wherever he needed to go. Sometimes I would bring him up to the block so we could just sit and talk.

On February 21, it was a Tuesday or Wednesday, Dawud came to watch a charity basketball game. When I took him back to the infirmary, he told me he was feeling good; he was preparing for an interview for commutation the next day. We made plans for when I would pick him up to take him to the interview. Then, I gave him a hug and told him I loved him, like I always did. He was like, “Alright, little brother, I love you, too.”

The next morning, before count had even cleared, they hit my door. I noticed guys were looking at me with weird faces, and I knew something was wrong. Someone told me to go into the sergeant's office, and when I got there, the counselor and unit manager were both there. A guy named Sul, who was close friends with Dawud and I, was also in the room. When I saw tears in his eyes, I knew something had happened.

Dawud died on February 22, 2024. We were cellies for eight years. He believed in me when no one else did—before I even believed in myself. He was the most consistent person I’ve ever had in my life. Losing him was the most painful thing I’ve ever gone through.

We had a memorial for him in the chapel, and it was nice to hear guys speak about how much Dawud meant to them. All his belongings were still in the cell with me. It took me a minute, but I packed it all up and sent it to his family. I’ve still got all the birthday cards he gave me and notes he wrote me. I read through them every now and again, and they always lift my spirits. Dawud changed me. I wouldn’t be who I am without him, and I’ll carry his spirit with me for the rest of my days.

*****

In December 2023, I was resentenced following a legal battle that started over a decade earlier with Commonwealth v. Batts. I’m Qu’eed Batts.

In 2007, I was tried as an adult and convicted of mandatory Life Without Parole (LWOP). I appealed that ruling on the grounds that it is a cruel form of punishment to sentence a child to Death By Incarceration, and it violates the eight amendment. My appeal was granted in 2009, but my case was pending because the United States Supreme Court was hearing similar cases from other states. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory LWOP for juveniles was unconstitutional. They based it on brain science that said children have diminished culpability and greater capacity for change, and said it violates the eight amendment that forbids cruel and unusual punishment.

Once the U.S. Supreme Court handed down their decision, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court took up my case that made the same claim under the PA state constitution. I was not prepared for the pressure I would feel having such a high-profile case. I was 21 years old at the time, and there were roughly 600 people in Pennsylvania who were sentenced to DBI as children whose chances at freedom were dependent on the outcome of my case. That’s not to mention all the people writing news stories about me, many of which perpetuated the fear mongering that fuels tough-on-crime policies.

In March of 2013, the PA Supreme Court ruled in Commonwealth v. Batts that mandatory LWOP for children under 18 years old is a cruel form of punishment that violates the PA Constitution. We won! This meant that almost 600 people in Pennsylvania who were sentenced to DBI as children would be resentenced. The new guidelines said that if you were 14 or younger when you committed first degree, you would be parole eligible after 25 years. If you were 15-17 when you committed your crime, you’d be parole eligible after 35 years. The only problem was that the decision was not retroactive. Those sentencing guidelines would apply to all future cases, but not those of us who were sentenced for cases before 2012. We would be resentenced individually, and it was up to the judge in whatever county we were sentenced to decide our fate.

In the months to come, I saw a lot of child lifers win their freedom as a result of the ruling, especially guys who were resentenced in places like Philadelphia, where they typically followed the new guidelines in their resentencing. My excitement quickly dissipated when I got back to Easton, PA and saw the judge who would oversee my resentencing. Unfortunately, sentencing is often less about the case at hand and more about the politics of the county you’re in. Northampton County is all about locking folks up and throwing away the key. I got resentenced to 50 to life, which is considered a “virtual” life sentence because most people with a sentence that long die in prison.

I’ve seen guys with three homicides who got 25 or 35 years to life, and they’re home now, which I’m not knocking because I want people to get their second chance. I’m happy to see them doing well out there. But then you’ve got a guy in another county who’s sentenced to 50 or 60 years for strictly political reasons—it had nothing to do with the details of their case or their behavior behind prison walls. They’re just not going to get a second chance, and that’s that. Because we technically won the case and so many folks gained their freedom, there’s no more attention on those of us who were resentenced to virtual life sentences. I don’t think folks realize how many of us were left behind. We’re still here and a lot of folks either don’t understand or don’t know how to articulate what happened to them.

*****

I work in the barbershop here at SCI Somerset. I started in 2017 at Coal Township as a student, got my license in 2020, and I got my manager’s license last year, which means I can own my own shop when I get out. At Coal, I was a tutor for students who were just starting out. I work from 8:00 – 3:00, Monday through Friday, and make about $100 a month.

The barbershop is a cool environment. Of course, we know we’re in prison, but we’re a little freer in here, at least in our minds. We get to offer a service people appreciate, make them look and feel a little better. And I like refining a skill that I can use when I get home. I’ve worked with some guys who got out and they’re making a good living for themselves now.

I turned 34 on April 18 of this year. At first, a lot of guards look at me like I might be a troublemaker because it’s always the young guys causing problems. Once I explain to them that I’ve been locked up for 20 years and they don’t have to tell me anything, they pretty much leave me alone. People don’t realize the lifers are the ones who keep the prisons in check. Even many of the guards are very young, so they bring the same hot-headed energy as the young guys in population. It’s the old heads who keep it together, and I guess I’m on my way to being an old head now that I’ve been down for two decades.

I got a chance to connect with my daughter in recent years, and we talk every day now. I’m grateful we can speak freely now. We’ve been able to work through the pain she felt in my absence and the struggles I feel not being able to be there to protect and provide for her. She’s in nursing school now, and she’s doing great.

I am actively fighting to make it home, and I believe I will. When that time comes, I believe it will be best for me to settle in the Carolinas. I have family support there and my girlfriend lives there. My dad has settled in Charlotte and we have built a very strong connection. He knows the type of help I will need firsthand coming out of prison.

I’m passionate about helping kids who are at risk of the kinds of abuses I endured in the system. I could see myself connecting with kids through coaching and then being able to serve as a mentor to them. There’s nothing I’d love more than coming alongside kids who are 12 or 13 years old, to help them see they’ve got more options than to turn to the streets. They just need people to believe in them and give them a chance.

I'm not angry anymore. I was very angry when I was younger. We talk about second chances for folks who are incarcerated, but honestly, I didn’t feel like I had a first chance. I’m not trying to make excuses for my behavior—I took a life, and I will work to make amends for that until the day I die. What I’m trying to say is the state snatched me from my family when I was 5 years old. They shuffled me around from house to institution to homeless shelter to solitary to cage after cage after cage, and it was until I met Dawud that I realized I could take ownership over my own life. He woke me up to the agency I had—my capacity to make a difference in people’s lives, for better or worse, including my own. He taught me the importance of the collective, that we all essentially belong to one another.

During my first stint of being resentenced, I met a young man that was 18 years old in Northampton County Prison. He was facing a future that meant he would spend the rest of his life in prison for a crime that was committed when he was a child. I immediately felt the obligation to be a positive example for him, just like I needed when I was his age. I knew that I couldn’t just bark orders and tell him how he had to change—I had to show him how I had moved in a different direction in my own life. Now he’s around 24 years old and we still stay in contact. I can tell he’s coming into a state of consciousness himself. I did for him what Dawud did at the beginning of our friendship. He planted seeds in me, and now through the work I’m beginning to do and the way I carry myself on a daily basis, we get to watch the seeds blossom.

If you would like to send Qu'eed a note, you can write to him at:

Smart Communications/PA DOC

Qu'eed Batts #HG8577

SCI Somerset

PO Box 33028

St Petersburg, Florida 33733