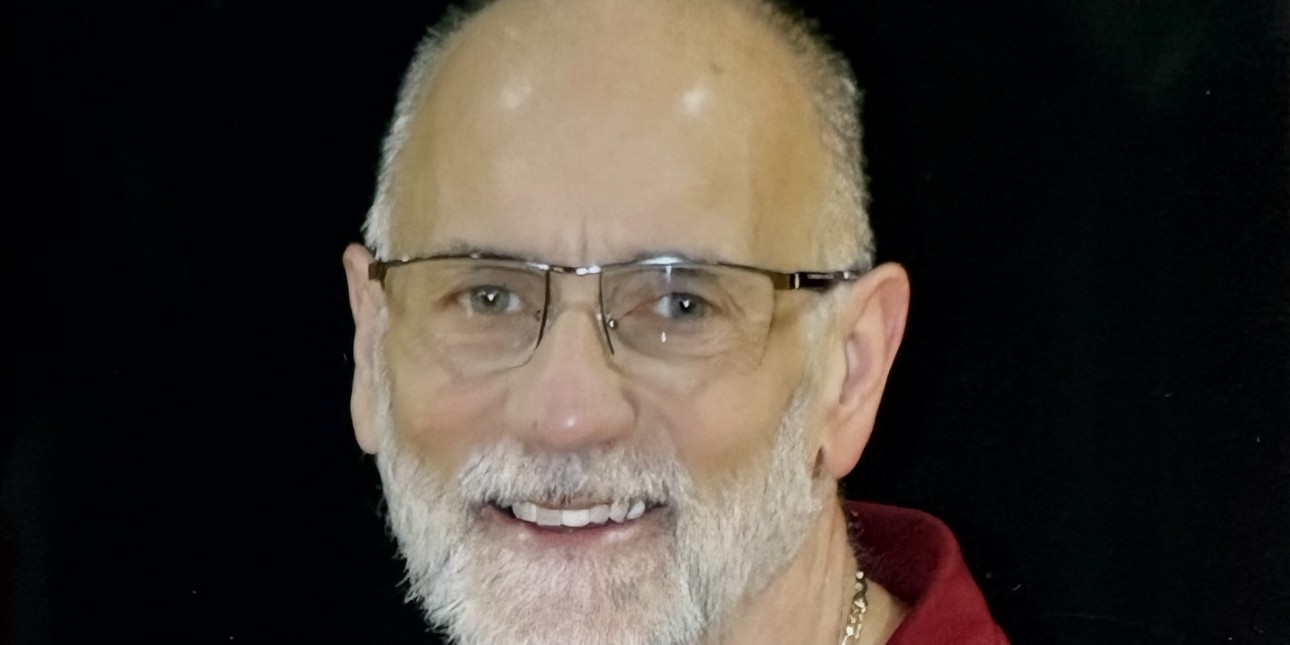

Richie Marra: The Entrepreneur

Richie Marra runs the A/V room at SCI Chester. He was awarded Prisoner of the Year by the PA Prison Society, and he is one of the 64 people living on the Scandinavian Unit, an experiment based on Nordic prisons where incarcerated people have more autonomy and more humane living conditions.

I just heard a prompt this week that is something I've been thinking about for some time: If the world only focused on the worst thing you ever did, what would the world not get to know about you? Well, let's give it a whirl.

Every day, I wake up around 5:00 AM. I turn on the news, make my bed, and prepare my breakfast. After breakfast, I clean up, get dressed, and get ready for my morning workout. At 6:30, they open the doors, and I head to the treadmill or elliptical to run for the next 50 minutes. By 8:00 AM, I am sitting in front of a computer screen at work in the Audio/Video Room.

As far as prisons go, I'm one of the lucky ones. Out of 39,000 people incarcerated in Pennsylvania state prisons, I'm one of the 64 incarcerated individuals living on the Scandinavian Unit at SCI Chester — a specialized unit that is modeled on the prison system in Nordic countries where incarcerated people live more closely to the way they are expected to live when they are released. It is part of a study being conducted by Professor Jordan Hyatt from Drexel University.

When visitors come through for a tour of the unit, they often visit my cell, where I get an opportunity to tell them about the unit and what it’s like to live here. I tell them about the sense of calm. I didn't realize how abnormally I had been living until I came to this unit and felt the physical relief of not having to be on point all the time. Prison life trains you to be hyper vigilant, especially sharing a cell with another person. On this unit, I don't have to lock my door or my locker. I don't have to rush to the phone to make sure I get a phone slot. There isn't the mad rush for everything. A common understanding in prison is, "you snooze, you lose." It wasn't until I got relief from that environment and sunk into this sense of calm that I could look back and say, "that was no way to live — it wasn't normal what I was dealing with every day."

I grew up in a warm Italian family in South Philadelphia. I went to Catholic school and had lots of friends. No one in my family was ever in prison. I didn't know anyone who was in prison. My brother and I played in a band together. I played the drums, and he sang and played the guitar.

My father and I were very close. I worked with him on the weekends, and we shared a lot of the same interests - cars, sports and business. He admired that I was a hard worker who took initiative. If there was a problem, I'd figure out how to solve it, and he loved that about me. He made me feel like I was the pride of his life. He would ask me,

"Rich, what did you learn today?" If I said "nothing,” he'd say, "Every day you learn something. Don't ever let a day end without recognizing what you learned." That has become a habit of mine that I still do today. Sometimes a bad day can turn into a good day just by recognizing something I learned.

Everything changed on Memorial Day in 1978. I was 14 years old and just finishing my freshman year. I was playing softball with my father at a family picnic. I kept bugging him to take me driving and he would always wiggle out of it — "your mother would kill me," or he would say, "tomorrow." Today, I thought, "he's going to take me driving." As we left the field and were walking back to the picnic area, he knelt on the bat he was carrying as if he was catching his breath. He was only 39 years old, but he'd already had a heart attack when he was 36, so I was worried. We didn't live far away, so he said, "run home and get my pills on the kitchen table." I took off running as fast as I could — I think I broke a window to get into the house. By the time I got back, he was on the ground with everyone around him waiting for the ambulance. I remember feeling so helpless seeing my father lying there unconscious. The ambulance came and took him to the hospital, but he never regained consciousness. Life would never be the same.

That summer I stayed around the house a lot. I felt anxious about everything. I worried about what we were going to do for money, what would happen to the house. When work needed to be done on the house, I figured out how to do it. All the neighbors would say things like, "Oh, Richie's stepping up — he's the man of the house now." But the truth of the matter is that I felt very unsure of myself. Looking back, I was just too young. I started putting on a front because I didn't measure up to how I thought others saw me, but I wanted to. I wore a mask based on what I thought others expected of me, and I made everyone think I was okay. But I was really hurting inside — just a scared kid trying to be a man, and afraid of showing any weakness.

To make matters worse, I grew up in a neighborhood where everyone had money; we didn't. So I became a little insecure about what I didn't have. My grandmother and grandfather bought the house in an up and coming neighborhood in 1960. When my grandfather died in 1971, we moved in with my grandmother, and my mother and father took over the mortgage. It was a great community with cul-de-sacs, garages and driveways. I had a lot of friends in the neighborhood and it was a fun place to grow up. As I got into my teens, I began to get embarrassed by some of the things we didn't have — like new cars, vacation homes, and the little things I couldn't just ask mom for. If I wanted something, I learned to work for it. I cut lawns in the summer, shoveled snow in the winter. I washed dishes at a catering hall and made pizzas at a local pizzeria. I even had my own paper route, delivering the Philadelphia Bulletin in 7th and 8th grade.

As I started my freshman year at St. John Neuman High School, I immediately got involved with extracurricular activities like student council, the track team, and I became the underclassmen editor of the yearbook. I ranked 57 in a class of 511, which I thought was pretty good. I was proud of myself. I had a dream of going to college for finance and business. After my father died in late May, I began to lose interest in school. By 11th grade I was ranked 350 in a class of 424. I withdrew from a lot of the extracurricular activities. In 1980, I began my senior year at a public high school, South Philadelphia High, known as "Southern.” I was suspended a few times for not going to school, and I barely graduated. My mother was on me about it and she reminded me of all the dreams I once had.

After graduating high school, I enrolled in Community College of Philadelphia in September 1981. I was doing well with a 3.3 GPA, but things were moving too slow for me. My friends were not pursuing education. They were working or pursuing business interests. I would go to school during the day, work after school and hang out with my friends at night. It was an impossible situation, I thought. I had to get a full-time job, maybe start a business, so at the end of the year, I decided to "take a break" from school for a while.

I was 18 years old. I immediately began landscaping in New Jersey. Then I got a job working at a steak house where I eventually became the manager. I was working a lot and saving money. I bought a hot dog cart, a fixer-upper property and I made an investment in an IPO that paid off. I was coming into my own. I was gaining confidence. But I was also making a lot of bad choices. Few people were questioning me because I had always seemed to be on top of things.

By the time I was 20 years old I was serious with one particular girl, and we had plans for a future together. All my friends' girlfriends were all friends, so we were a close-knit group. We went to the movies together, out to eat, and down the shore.

I had just turned 22 years old when I made a fateful decision that would change everything. I often wondered why I felt like I had to carry a gun. Somebody asked me that one time, and I said, "Well, to feel safe." And he said, "Yeah, but you didn't live in a bad neighborhood." I told him, l wasn't afraid physically; I was afraid of looking weak or feeling small." I wasn't a big guy and backing down from anyone wasn't an option. It doesn't make sense to me today, but somehow having a gun made me feel like I could hold my own.

We were at an engagement party that night, me, my girlfriend, and all our friends. After the party, we agreed to meet up at the club. I arrived at the club with my girlfriend and another girl. Just at the entrance of the club, I got into an argument with a group of guys. When the doorman got in between us, I left with the girls. I drove them home but returned to the club about an hour later. I went up to the second floor bar where I usually hung out with my friends. After a half hour or so, I joined my two friends by the balcony. They were asking where the girls were. As I was telling them about the argument earlier, I saw someone walking from the bathroom who I recognized as one of the guys from earlier. I said to Louie, “I think that's one of the guys." Louie runs over to him with a glass in hand, throws it at him, and they start throwing punches. Before I know it, I've pulled out the gun. I jump over Louie's shoulder, and I fired a shot. I thought I was just pulling it out to intimidate the guy, but I fired it, and we all scattered and ran out of there.

I didn't have a violent history. I was in two fist fights in my whole life, and I haven't been in a single fight since that night. As a matter of fact, out of all my friends, if they took a gun off a guy in a bar or something like that, they'd say, "Give it to Richie. Richie wouldn't do anything stupid." And here I am, 38 years into a life sentence because I took another man's life.

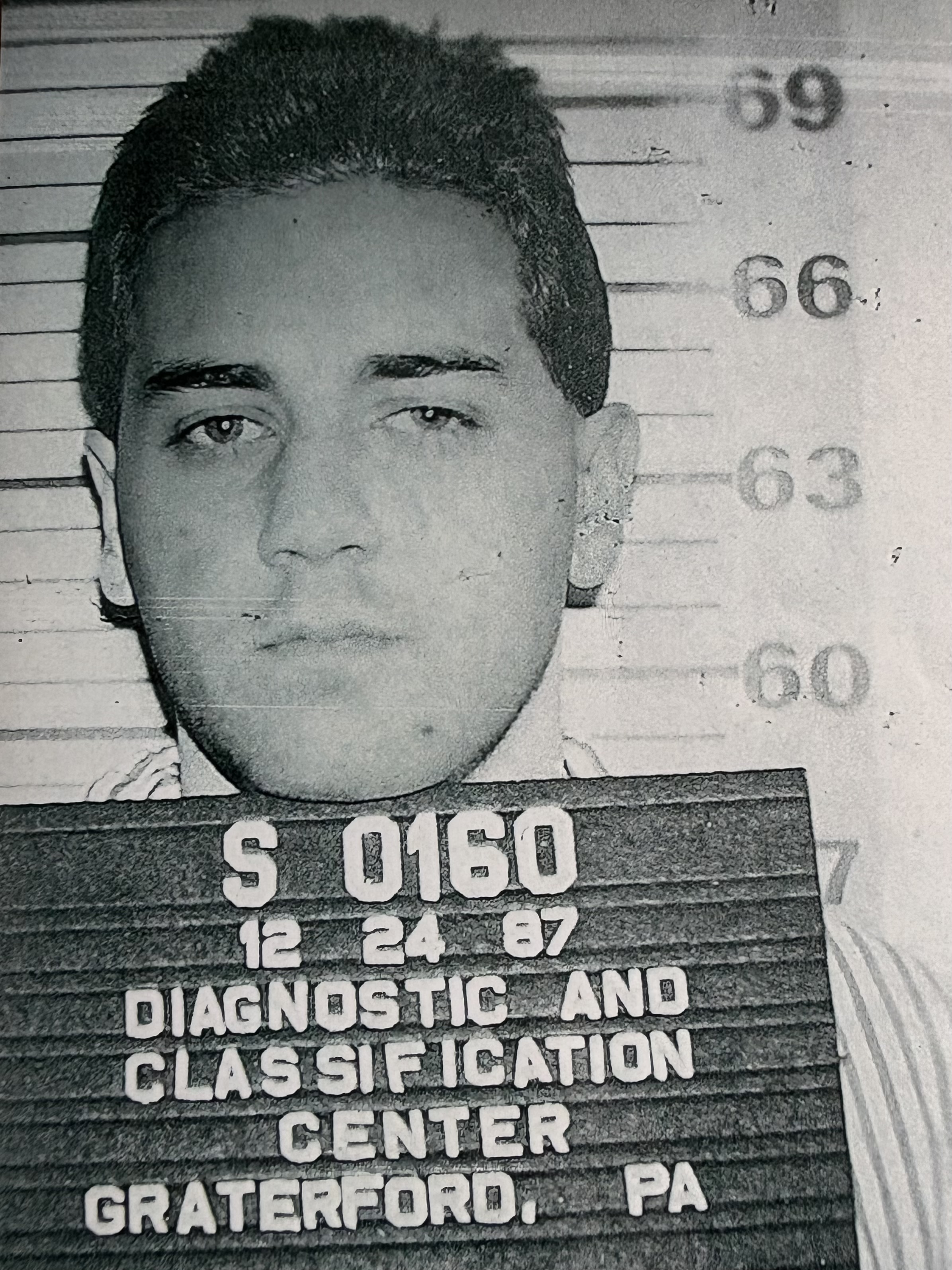

This was January 1986, Louie, Jeffrey and I were arrested six months later and were released on bail. We went to trial together in 1987. Louie and Jeff were found not guilty. I was convicted and sentenced to a mandatory life sentence.

I never took responsibility from the start. I was fighting tooth and nail to hang on to my life. I refused to let myself think about the person I killed or his family. I don't think I wanted to face how terrible a thing I did. I didn't verbally claim my innocence, but I didn't talk about it or admit to it either. I just shut down. After coming to prison, I went through something like the five stages of grief: denial, anger, depression. I kept thinking, "This can't really be the rest of my life. It can't be."

Several years into my incarceration, I began doing a lot of self-reflection and I was taking positive steps to change. My family was happy to see me engaged and being productive. But something was gnawing at me. I wasn't being honest with my family about my crime. It wasn't until I was about five years into my sentence that I finally confessed to my mother. I thought I would take this to my grave. I was so ashamed to tell her that I killed another mother’s son. Well, my sister was coming to visit me one day while my mother had a doctor's appointment, so I knew it would just be me and her. As I waited, I remember thinking, "maybe I should tell Marcie first and ask her if she thinks I should tell mom." Just the thought of this had me pacing my cell, feeling like I might have a nervous breakdown. As we sat down in the visiting room, I said, "Listen, I've got to talk to you about something," and I knew she could tell by my body language — I just broke down as I told her. She agreed that I should tell mom.

A couple of weeks later, I told my mother. She broke down too and said, "I'm proud that you're taking responsibility." Then she said, "But you've got an obligation now to do something with your life. You've got to make amends with the way you live the rest of your life. I don't ever want you to give up."

That was the beginning of when things started turning around for me. I had to get out of denial and come clean in order to move through the shame that bogged me down. I don't know where I'd be without my family. So many times, I've wanted to give up. But my family — really my sister, she wouldn’t let me quit, no matter what. She just wouldn't let me.

Over the next four years, I went back to college and received an Associate's Degree in Business. I completed about 5000 hours of vocational trades in Building trades, Electronic and Computer Technology.

In 1996 my mother passed away at home—another turning point for me in my life. I never felt so much pain. For days everything was just BLACK. No hope. No desire for anything. Life was over. The support and love from family and friends helped me to regain hope — slowly. As the weeks and months passed, I began to take the focus off myself. I became involved with community activities in the prison. I stopped resisting the lack of control I had in this new world. I still tried to plan my days, but I learned to be more flexible, and humble. I was maturing.

From 1997 through 2002, I became a tutor for the GED Program; I facilitated a new civics program for new arrivals to the prison; I became the secretary of the LIFE Association; and I got more engaged with the lives of others. I continued to take classes and programs to learn about myself and how I could help others.

Life has a way of giving you opportunities you ![]() don't expect. In 1998, while finding my footing with my job, the music program, community work, and finding a sense of purpose, an opportunity came my way for a promotional transfer to a new prison in Chester, PA.

don't expect. In 1998, while finding my footing with my job, the music program, community work, and finding a sense of purpose, an opportunity came my way for a promotional transfer to a new prison in Chester, PA.

Unfortunately, all I could see was a new prison that would likely be more limiting and take me away from what I was already doing, so I declined. It didn't take long to think that maybe that was a mistake. It was only ten minutes from home! Why did I say no!

Four years later, in 2002, I got another opportunity for a promotional transfer to SCI Chester. This time, I took it. As I prepared to leave SCI Dallas for SCI Chester, I wrapped up all my affairs with work and the LIFE Association — meaning I relinquished all my responsibilities and began my goodbyes. In the few days before I left, I was at peace. My mind was clear to think about the future. I had no specific plans of what I would do at Chester or any expectations of what Chester would be like, but I felt confident that I would be okay. The last 15 years gave me that confidence.

Although I wasn’t being released from prison, it was a new beginning filled with a lot of unknowns. I wanted to take it all in without overburdening myself with too much too quickly. At Chester, I spent several days getting settled and meeting the men and staff. I spent time in the yard every day to run the track. After a few weeks, I was offered a job as a tutor for Business Education and I accepted it. The classroom was filled with computers, which I had always been interested in. I tutored the students on Microsoft’s office applications. I enjoyed being around men who were trying to better themselves and develop new skills. Unlike tutoring GED students, this class wasn't mandatory. Since I was always eager to learn, I felt everyone could teach me something.

I soon got involved with the music program at Chester. I played the drums with a few bands and we put on shows for the inmate population. I became secretary of the Inmate Improvement Organization and I sat on a few committees and focus groups. In 2003, I was asked by the Activities manager to help the Audio/Video Program build a database to keep track of their VHS tapes and create a scheduling system for them. The Activities manager at that time had bigger plans for me.

The AV Program set up the sound system and stage in the gym for all the events held at Chester, including our inmate concerts. The sound was not very good. I often asked the inmate working in the AV Program at that time if he could do this or that to improve the sound, but he didn't see anything wrong with it. Eventually, he turned it back on me and said, "If you think you can do it better, give it a try." I then began to help out with the sound set ups. I didn't know anything about sound, but I couldn't do worse. So I called my brother and began asking him questions. He ran the sound system for his church. Between my brother, trial and error, and reading a lot of books and trade magazines, I began to figure things out.

It wasn't long before the Activities manager approached me about working full time in the AV Room. I didn't know anything about AV, but I was up for the challenge, so I accepted the job. Then a few weeks later, he hired another guy seven years older than me who came to prison when I was still in grade school. His name was Ezra Bozeman, I called him "Boze," and we became great friends over the years. We spent most of our time in the AV Room — from 8:00 AM until 8:45 in the evening — counting out in the AV Room most days. We did this for a few decades, earning our 10,000 hours and learning a lot. We did good work together.

Boze passed away in 2024. He came to prison when he was 19 years old. He had a stroke and became paralyzed from complications of surgery. Although he wasn't terminal, he asked for compassionate release. With support from Governor Shapiro, they ordered him released. He was first released to a hospital with plans of going to a rehabilitation center, but other conditions added to his troubles and he asked that they not treat him any further. He passed away that day at 69 years old. I learned so much about people, about myself, and all that is possible. What my father told me so many years ago still resonates with me. I am always learning as I reflect on my days.

Back in 2003, I dug into my job in the AV Room—I wanted to know everything. I was always the type of person who had to know why, or how. This gave me ways to use what I learned to come up with creative solutions to problems. I learned how to use all the equipment: the video cameras, the still cameras, the sound board, video mixer and the entire PA system. I would read all the manuals and get books at the library. If I met someone, staff or inmates, who knew something about this stuff, I picked their brain. Eventually, I came up with ways of setting up the sound system, and I developed a workflow to accomplish our recordings of events. We set up the sound and recorded all the events held in the prison: graduations, concerts, guest speakers, guest performances, sporting events, and much, much more. I learned how to edit video and sound and we'd show the videos over our two in-house cable channels. Over the years, we went from VHS tapes to DVDs. Now we are working with High Definition and using editing programs like Adobe Premiere Pro and Avid Media Composer.

From 2003 through 2015, I participated in many classes and programs, worked on fundraisers, facilitated groups, and met many people. It was also a time for deep reflection about who I was and the great harm I caused. I went through victim awareness and violence prevention programs. And I would be reminded again and again how much pain I caused the victim's family. It only took one crucial bad decision and the ripples never end. I'm reminded of this every day by watching my own family live with the consequences of what I've done. My family has been instrumental to my mental health and a constant source of support over the years. So whenever I can do something to make them proud, it means the world to me.

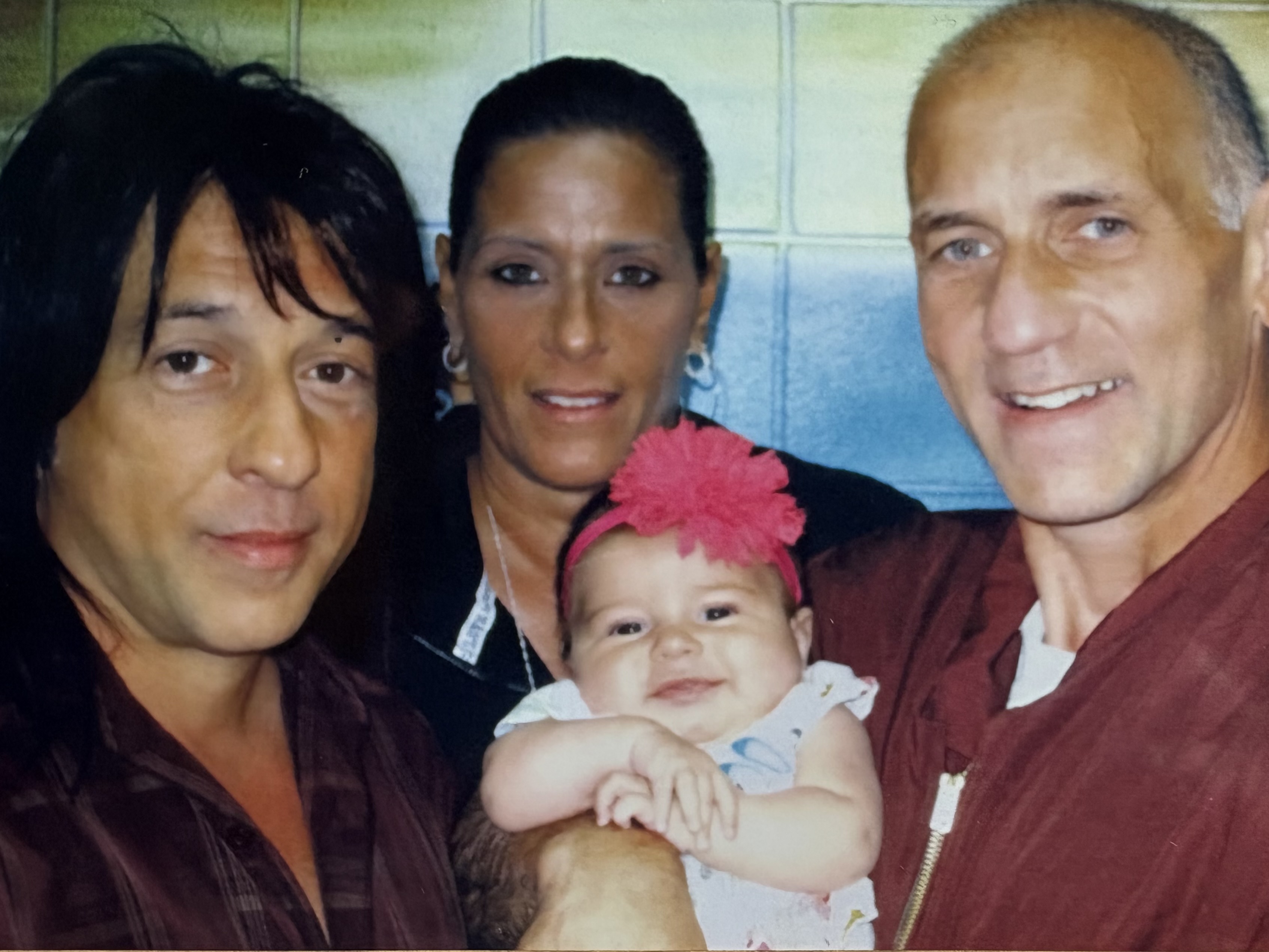

When The Pennsylvania Prison Society honored me with their Prisoner Of The Year award for my "quiet influence on others," my sister, Marcie, received it on my behalf at the Prison Society's annual dinner. She was so proud. My sister and I are very tight. She visits me every week, and that hasn't changed for almost four decades now. I talk to her every day on the phone. Our brother, Joey, is the only one who had children, my niece and nephew. They've been coming to see me in prison since they were infants. Now, they are both married and take their children to see me — my grandnieces and grandnephews.

Sometimes people come into your life and opportunities come your way that you can't plan for. In 2016, an extraordinary leader became superintendent at SCI Chester. Her name is Marirosa Lamas. She knew how to make everyone — residents and staff — feel like they were a part of the mission to get things done. She brought a TEDx event to Chester, and followed that up with the first ever Prison CPAC in 2019, held and livestreamed right from our gym. Prior to that, I put together these video shorts that highlighted our volunteers, special programs and events that our superintendent wanted to lift up at Chester. I was developing skills that I could use to contribute and be part of the bigger missions of Chester. This gave me a sense of purpose.

In 2017, SCI Chester hosted the warden from Holden Prison in Norway. They shut SCI Chester down for a day and had prison staff from across the whole state of Pennsylvania come to Chester to hear him speak about a transformation they had experienced in their carceral system. He said, "Thirty years ago our prison system was a mess. It was terrible. We realized the vast majority of these people would be coming back to society, and the goal was for them to be more responsible, healthier people. When we stopped and asked whether the environment we created for them would lead to that outcome, we realized we needed to rethink our entire corrections system."

The way the Nordics think about prison is that being separated from society, from your family, that's the punishment. They don't need to be punitive beyond that. They want people to experience the normalcy of their lives back home so they can become more responsible.

In March of 2018, I was granted a public hearing with the Board of Pardons for a commutation of my life sentence. Prior to this, I was interviewed by the Secretary of the Department of Corrections and received their full support. I had served 30 years at that time. The public hearing went well. Seven People testified on my behalf; five of them I met during my incarceration. Unfortunately, I did not get the unanimous votes that are required. I received 2 out of 5 votes.

In 2018 the Department of Corrections in conjunction with Drexel University began a plan to transform a unit at SCI Chester and conduct a study of the Nordic prison system the first here in the United States. By 2019, the transformation began, officers were trained and the plans were set in motion. SVT, a Swedish film production company, began filming the transformation for a documentary. I was also recording the progress of the unit for SCI Chester. The production company would eventually use some of our footage for their documentary. I was proud of this.

The Scandinavian unit has 64 single cells. It hosts a kitchen with four stoves and ovens, refrigerators, air fryers, rice cookers, toasters and other appliances. The unit has a 75 gallon fish tank, comfortable couches, workout equipment and more. The cells are equipped with 19" flat screen TV's on the wall, mini refrigerators, a large standing cabinet, a desk, a personal chair, and a finished floor.

Residents on the L.S. Unit are picked by lottery from the general population based on various tiers of sentences. The lottery is meant to preserve the integrity of the study so that it has a good sampling of the general population. Six lifers were chosen by the initial lottery system because lifers represent about 10% of all DOC prisoners, and they have some impact on the prison population as a whole.

Those six lifers were identified on March 6, 2020, and moved over to the new unit that day. I was one of them. They had us move over first to help get the unit ready for the May opening. They were looking for feedback from the six who collectively had served more than 200 years. We came up with a scheduling system for the laundry room, a mission statement, and codes of conduct for our new community. We pushed for not using a schedule for the kitchen. Our experience taught us that sometimes having things happen organically makes the most sense and is the most efficient. People usually figure out how to get in where they can fit in. We argued that a no-rules-until-we-need-them should work best. And it has worked perfectly for more than three years.

They refer to us six as the "mentors." I think of mentors as people who live by example and that others want to emulate. I hope we are truly seen that way.

By late March of 2020, the program was put on hold due to Covid. In September of 2020, I was granted reconsideration by the Board of Pardons and granted another public hearing. The District Attorney's office did an evaluation of my case, along with a review of my prison record, and supported my application for commutation with the Board of Pardons. This time there was victim opposition at the public hearing, which was held via Zoom. The application was denied 0-5. With victim opposition, it makes it almost impossible to be granted commutation, regardless of what I do with my time. This was a huge blow for my family and all the people who supported me. It took some time to deal with this — not just being denied commutation, but also realizing how much my actions continue to impact the victim's family. It was the first time I ever heard the family speak.

The six mentors remained on the Scandinavian Unit for some time before they had to use it as an annex for Covid patients. Then we returned in June 2021 and began preparing everything again. We painted, cleaned, and tested out shopping at ShopRite.

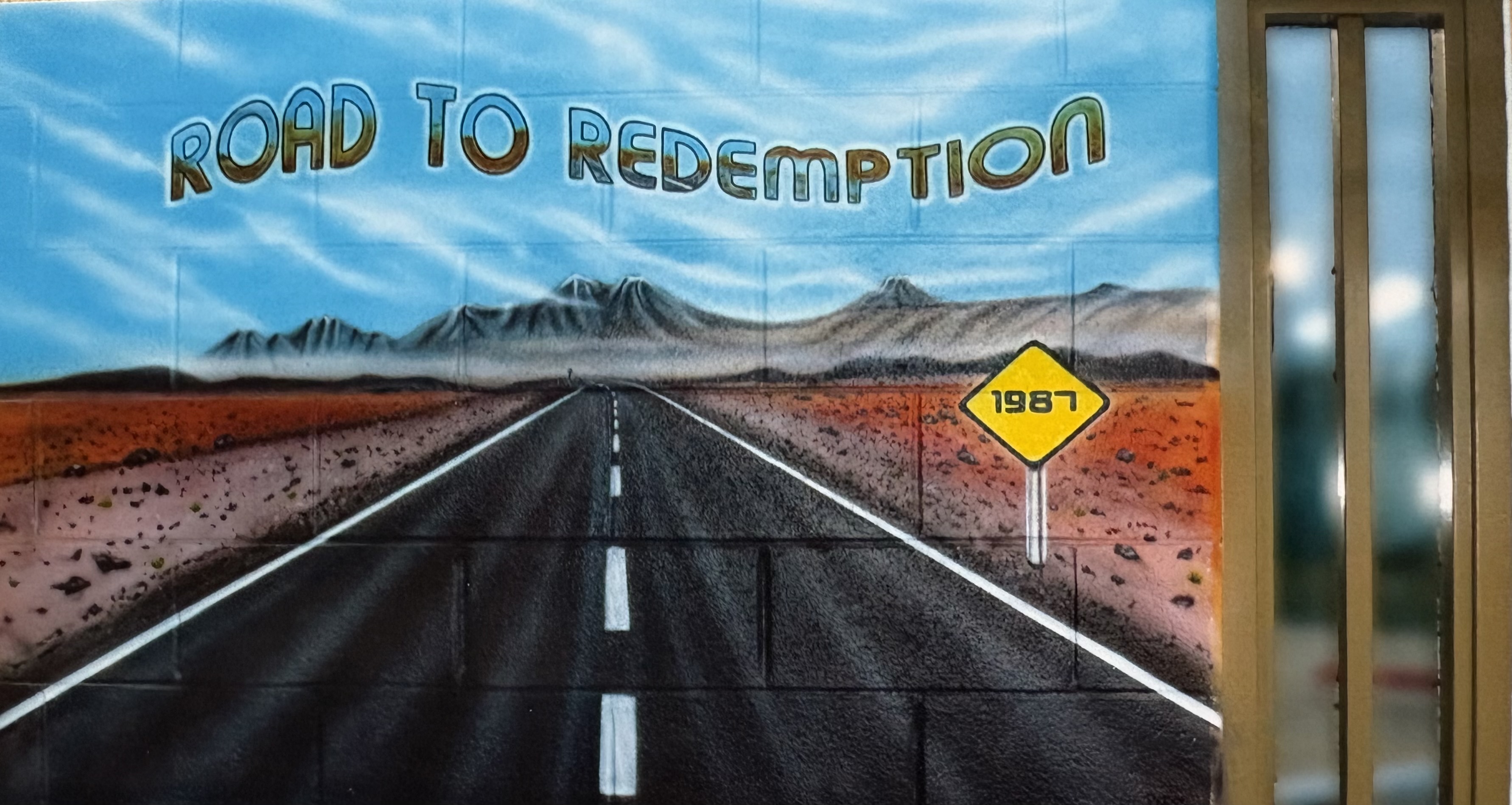

We were allowed to put murals on our walls. One of the mentors, Eliezer Perez, is an amazing artist. I designed a mural that I asked him to paint on the wall of my cell. It is a large picture of a road that vanishes or narrows into the distance. Above it, in big letters, it reads, "Road To Redemption." And that's how I see redemption — not as a destination, but as a journey, or a way I live my life. I owe a debt I can never pay; that can never be redeemed. But that doesn't mean I can't live my life to benefit others. And that's what gets me up in the morning.

The first cohort of residents were picked on May 4, 2022, and on May 5th, there was a "live opening" with big fanfare and dignitaries from around the state in attendance.

People from all over the world have toured the unit. We've had prison officials from many different states, the UK, South America, the Governor's office, Attorney General's office, parole agencies, re-entry programs, District Attorney's office, Department of Corrections from various states, and more. When they tour the unit, the contact officers usually bring them to my cell to show it. They always ask me to share a little about what it's like living here. I tell them the way prisons normally function is debilitating for people. They come to prison and everything is done for them. Food is cooked for them, laundry is done for them, they are told what to wear, when they can work out, in addition to the many other things prisoners don’t usually have to be responsible for.

A sense of normality is woven into every aspect of life here on the Scandinavian unit. For example, we have the freedom to plan our own days. We do our own laundry and iron our clothes. We are in a better place to read books, go to school and be productive. We even get to wear nice polo shirts with a Scandinavian crest sown into it instead of state brown prison shirts. Somehow, that makes us feel more normal.

Here, we get to make a lot of decisions that we haven't been making for some time and frankly have been out of practice with. We shop for food. We learn what to buy, what not to buy, how to budget our money. We decide when we are going to eat, what we are going to eat, and we learn to plan out our days. Do I need to take something out of the freezer? Do I need to do laundry today? When will I work out? It's easy to take for granted all the little decisions that a normal person in society makes every day. Being removed from society and cut off from our families is the punishment. But it's humanizing to have some agency – to get to make choices and let our guards down.

A retired superintendent Marirosa Lamas used to say, there are two big equalizers in life: The first was food. She would point out that "people feel warmth, people love, and people share when food is around." People open up to you in ways they never would, when the’ re sitting beside you and breaking bread together. "The other is the unconditional love, support and recognition from our animals. My belief is the best that we have in ourselves can be seen in the eyes of a dog." We certainly had the food, but because of the study, we weren't able to have pets on the unit.

On most general population units, everything is more regimented. The doors open for movement at 8am, when you'll go to work, school or the yard. Then every couple of hours, you get locked up again. Lockup for the night is at 9:00pm. In most prisons, people spend upwards of 16 hours a day in their cell. Here on the Scandinavian unit, the doors open at 6:30am and the residents are only locked in during the noon and evening count for about 30 minutes. Lock up for the night is at 11:00 PM.

Another thing that sets the Scandinavian Unit apart is the officer-to-resident ratio. On a regular unit, you'd have one officer to oversee 128 residents. Here, we only have 64 residents, but we have three officers. That creates less noise and less stress for both the residents and the officers. Rather than calling them correctional officers, they are referred to as contact officers. Each officer is assigned to a number of residents and act as a counselor of sorts. They practice dynamic security — that means each person, each situation, is handled differently. To do that, they get to know each resident personally. In a typical prison, fraternization between officers and residents is forbidden. But the Norwegian people see that as backwards. They say, "How can you support the residents if you don't know them? If a guy is having a bad day, you don't know how to read him and what he might need." So here, the officers spend time getting to know us. They can cook with us, play cards with us. That way, they know how to intervene in a way that's helpful rather than just punitive.

I believe the Scandinavian model is a great concept and will change lives. But there has to be buy-in from officers and prison administrators. Furthermore, the whole prison needs to follow this model as it does in Scandinavian countries. Having only one of these units out of 14 at Chester makes it almost impossible to change the culture at any prison. How long before the old ways of doing things seeps into the Scandinavian unit?

Gina Clark became Superintendent soon after the opening of the unit. Superintendent Clark also loves animals. She believes in second chances and has supported many of the men here when it comes to parole and commutation. She's not afraid of big moves to support what she believes, so she authorized the pets to be on the unit. We currently have two dogs and two cats.

Soon after the live opening of the Scandinavian Unit in 2022, Superintendent Clark tasked me with putting together a newsletter about the unit to inform residents and staff in general population about the unit and to dispel any rumors. I interview new residents for the newsletter a few weeks after they've settled in to get a take on their thoughts. They always have something interesting to say. Every 4-6 months, another lottery is held to fill the cells of men who've been released. Just before each lottery, I put a newsletter out. I'm getting ready to put out our 7th edition soon.

I've also facilitated several programs on the unit. I facilitated something I called "Community Dialogues" to get the guys thinking and talking about their plans after release and what they are doing now to prepare for that. I also facilitated a workshop on Stocks, Bonds & Other Investments. I'm currently working on a workshop to teach stop motion animation, and hopefully help some of the men find something they are interested in.

I've come a long way since 2003 with technical skills and creative skills. I love to work with motion graphics and software applications like Adobe After Effects. I continue to build on my 3D skills, building 3D models that I can incorporate into my videos. Editing and creating videos are my favorite things to do, and editing has made me a better cameraman and sound engineer.

The Scandinavian Program has given me even more opportunities to learn and grow. Several outside organizations have partnered with the Little Scandinavian Unit to provide educational and re-entry services. One is Wharton. Wharton Works, an arm of the Wharton School of Business, offers classes to the residents. They have been conducting classes since 2023. Classes include Financial Capability, Entrepreneurship, and Negotiations. They use the Socratic method to engage students in critical thinking, dialogue, and exploration of ideas. Classes are facilitated by MBA student professionals who have already been working in the business community. Classes are amazing, and I've taken advantage of every one of them. We just started Entrepreneurship II and a class on investing.

UpLift Solutions is another organization that has been coming in to help the men prepare for release. They will also support them for up to three years after their release. And a group of people from Villanova have been coming in to teach us about nutrition and how to prepare healthy meals.

Outside of the Scandinavian Unit, the RSO (Re-Entry Services Office) at SCI Chester partnered with Defy Ventures to train residents who will be going home within the next year. Defy is a 6-month entrepreneurial program that supports incarcerated people by making it easier for them to find employment after they’re released. Defy EIT's (Entrepreneurs In Training) are challenged to "defy the odds" in spite of their criminal history. It is led by retired and current business owners who work as volunteers. In November 2024, I got an opportunity to join the program when they decided to include a few lifers.

We just had a coaching session with business volunteers last month where we got to share our personal statement, our resume, and our business idea. I've been learning a great deal about how to present myself and my ideas. I've gained good insight and valuable feedback from the coaches.

They say that the best business ventures are to do what one knows. I came up with a business that I want to pursue—less for riches, and more to do what I love. My company is called Shine Video. I want to produce personal biographies or mini-documentaries for ordinary people who are celebrating a milestone and want to have a reflection piece to share with their guests, or a legacy video that they may want to leave for future generations.

I've come to believe that everyone has talent. Some people don't know what their talents are because they haven't been exposed to them. I believe if you want to help someone change their life, help them find their talent. And help them nurture that into a passion. That's where they will find meaning and purpose. And that, I believe, is what gives people a strong reason to be a part of community. It’s what changed my life.

I've heard it said that "Life is lived forwards, but understood backwards." When I was in my mid 20's, I was walking the yard with an older guy who was in his mid-50's. He was trying to assure me that there was hope down the road for me. Charlie said, "Rich, you'll be alright. You're young. You'll get out one day. Remember this: You don't start enjoying life until you hit 50. Me? My life's over."

Charlie had just come to prison at 55 years old with a 40-year sentence. I appreciated his opinion, but at that time, I didn't want to hear anything about being 50 years old. However, when I turned 50, I think I understood what he meant about really enjoying life when you turn 50. Around this age, I began feeling a sense of contentment about who I am – not being worried about status, or having to measure up. Today, I feel free to be myself.

Everything I'm doing today is a culmination of all the things I pursued and accomplished over my 38 years of incarceration. I could have never planned it out this way. I heard Charlie made it home some years ago. I'm still here. I'm 61 years old now. I have no idea what tomorrow holds—I just try to keep moving. I'll be up at 5:00 AM tomorrow morning, and every morning after that…until I'm not.