Living Hope: A New Essay on Second Chances and Freedom by Richie Marra

What does it mean to live with a death by incarceration sentence? And how do people serving such sentences try to effect positive change so they may one day rejoin their families and communities?

In this essay our friend, client and collaborator Richie Marra explores what it has felt like to remain captive in prison while growing older. He also speaks about how kindling the flame of hope has helped him keep going and transform his life for the better.

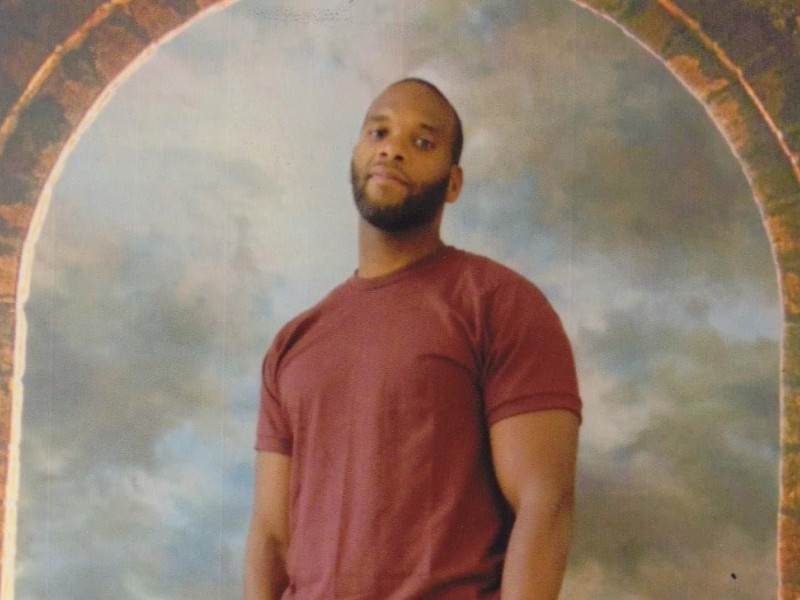

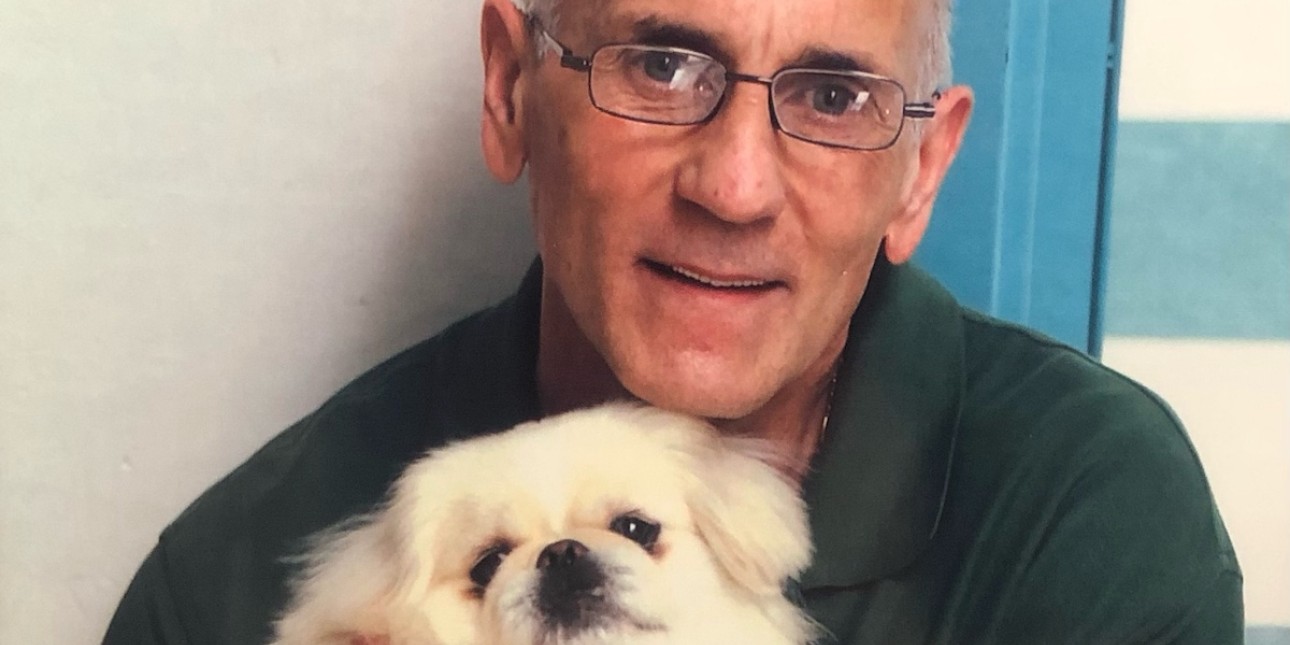

Richie is a living embodiment of what it means to turn one's life around and also what it means to refuse to let one's incarceration define you. He is well known at SCI-Chester where he leads the A/V program and for many years he resided on the honor block where the incarcerated people there take care of cats and dogs (like the one he is pictured with in the photo) for a local animal rescue. He now resides in ‘Little Scandanavia’, a unit that is an experiment in importing Norwegian correctional practices to America and where the people incarcerated there are allowed to do some humanizing activities such as cooking food together in a kitchen.

He’s worked with other lifers on principled advocacy efforts that would give people sentenced to life without parole a second look and a chance for freedom. In fact, his efforts and the efforts of his sister Marcie Marra, who has been a tireless advocate for him, have had a huge impact on our work at Amistad Law Project. Through persistent and clear dialogue they convinced us why it was important to take up the struggle at the Board of Pardons and help people come home through commutation while we engage in longterm work to win parole for lifers. Our work at the Board has resulted in us being able to play key roles in bringing some people home from prison and also helped to create meaningful policy shifts in the Philadelphia DA’s Office where they now have a fair process for commutation review that centers rehabilitation rather than re-litigating the applicants original offense.

In the years to come we hope Richie and his sister can reap the benefits of the work they have put in that has helped free others.

In the meantime we are grateful to call him a friend and client and excited to share this powerful essay with you.

Living Hope

By Richie Marra

Every August during my grade-school years I use to get excited about starting a new school year. It meant new clothes, new school supplies, a new teacher, and a sort of new beginning. It represented an opportunity to start fresh, to do better. I thought about this so often during my incarceration, wondering what got me so excited, so hopeful for the future. For as long as I could remember, I was always making plans. I wanted to go to college, become an accountant and businessman. I was going to build my own house, get married and have 4 kids (2 boys and 2 girls).

High School. College. Work. Friends. Girlfriend. Life was looking up. I had just turned 22 years old when l committed my crime. One bullet - and I destroyed two lives and two families. It still haunts me. l've spent countless days dreaming about the "what ifs": What if l didn't go to the club that night? What if I stayed in college? What if my father hadn't died? What would my family be like if I didn't...?

In 1987, I settled into my life sentence with the hope (and naivety) that I would win an appeal and go home. My life can't be over, I thought. Each appeal, each commutation application gave me the hope to keep moving on - a pacification, in a sense. But it served a purpose, otherwise, I don't think I would have been able to cope without hope.

I got into education and positive things from the very beginning of my sentence. I earned a college degree, received certifications in various vocational trades. I worked as a tutor in the Education Department for seven years. I've been managing the Audio/Video Program for the last 19 years. I served on several inmate organizational boards and committees, doing positive things like fundraisers for inside and outside causes, and serving in the local community. I became a mentor and a resource for the other men. I am always involved in one project or the other. Feeling the need to make up for what I did so many years ago is what I think drives me. And, of course, none of this would have been possible for me if I didn't come clean to my family early in my sentence and begin to take responsibility for my life.

Regardless of the good things I was doing with my life, none of the years were easy. There was depression and other setbacks, just like ordinary people experience in society. I lost loved ones. I lost appeals. I remember calling home as a twenty-something and hearing that my friends were going down the shore, they were getting married and having children. lt was heartbreaking to watch the world - my world - going on without me. That's the worst part of prison. Talk about FOMO.

I'm 58 years old today and all the dreams of my youth are long gone. I haven't hurt another soul since my crime at 22. l've learned my lesson well - and at every turn. But I don't beat myself up so much today. I found a way to forgive myself and enjoy the small successes in my days. Although I don't live my life as a "prisoner," sometimes I am reminded just how much I am.

I recently was taken to Wills Eye Hospital in downtown Philadelphia. lt was an opportunity - a sort of break - to see other people moving about in their days, get a look at all the cars, and the buildings and roads. lt was also a very emotional and sobering day. I was taken off the van right there in the middle of Walnut Street, in front of the hospital. Leg irons around my ankles, hand cuffed to a chain around my waist - traffic stopped in the street and people halted on the pavement. Everyone gave the two officers the right of way from the middle of the street to the hospital. They all watched me. I couldn't have felt any less of a person. I kept wondering what all these people were thinking about me. The officers "escorting" me treated me well, but oblivious to what I might be feeling. It was probably routine for them. Afterwards we drove down through South Philly to get on the Pratt Bridge. I haven't seen this part of town in 34 years. 34 years! I thought it would be exciting to see. Maybe if l was headed home. But I wasn't, I was headed back to the prison in Chester. And I couldn't wait to get there. Not really to be back at the prison, but so I could shut out all of what I can't participate in, or be reminded of, or made to feel so much less for.

No legislation or possibility of parole is going to take away my punishment, give me back my youth or allow me to live my dreams. But a parole bill will allow me to live the remainder of my life with some dignity - to be able to do normal things like care for myself and my own needs. And it will give me an opportunity to be there for my sister (who has been coming to see me at the prisons every week for more than three decades), along with my brother, my nieces and my nephews. It would also be nice to give back to the community that I came from. I still have a lot to offer - even if not a lot of time left to offer it. And l'm okay with that.

As long as I am able to care for myself and do for others, I still feel hopeful and excited about tomorrow. Maybe it's just something in me, like during my grade-school years, but I can always find the seemingly smallest things to get excited about. Perspective is a powerful and humbling thing.